Celeb Dirt To Be Sold? You Better Call Keith

A profile of the lawyer behind Trump "hush" deals

View Document

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

But from the outset of Davidson’s representation, Loyd said, there were red flags.

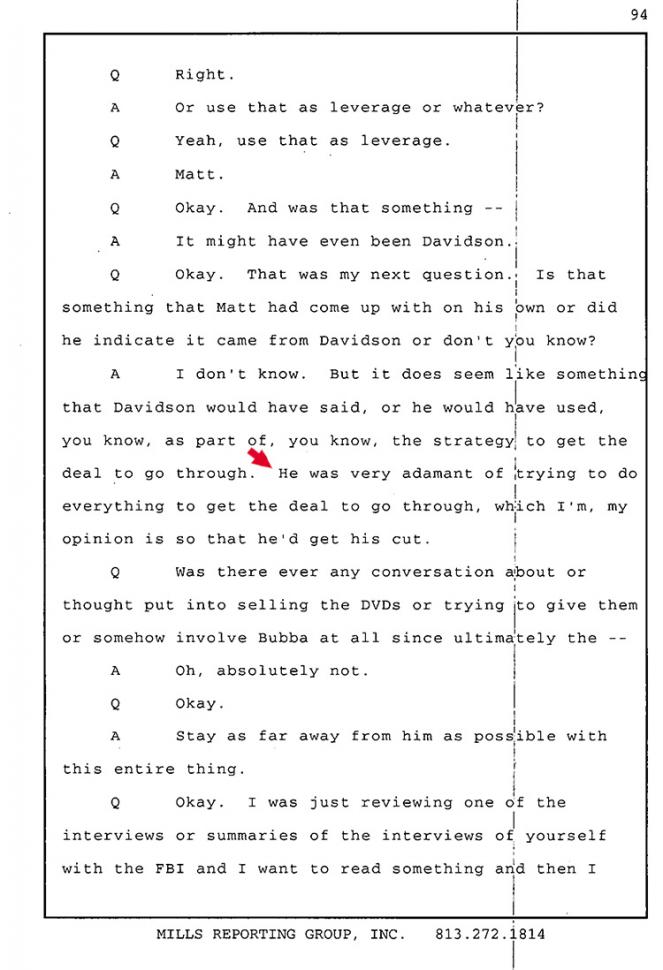

When Loyd told Davidson that he bought the sex tapes at a Clem “garage sale,” the lawyer rejected that story. Instead, Davidson suggested an alternative account: Loyd found the videos on a used laptop he had purchased. Loyd said that when he told Davidson that was not true, the attorney stressed that the laptop story was the one they were using. “I was like, okay, maybe this guy knows what he’s doing,” Loyd recalled. “He’s the attorney here.”

Citing attorney-client restrictions, Davidson would not answer TSG questions about the Hogan sex tape case.

After speaking with Loyd, Davidson immediately sent David Houston, Hogan’s attorney, an e-mail with the subject line “Hulk Hogan Tape.” Davidson asked Hogan’s lawyer to “call me regarding above.” After Houston’s assistant replied seeking further information (“Mr. Houston is unaware of whom you might be”), Davidson explained that he had been asked to  represent the “rights holder” of the Hogan footage and wanted to discuss the matter. Hogan’s lawyer agreed to a phone conversation, but wrote Davidson to say that his client was secretly taped, had never given consent to the video’s distribution, and was “distraught” over the Gawker leak.

represent the “rights holder” of the Hogan footage and wanted to discuss the matter. Hogan’s lawyer agreed to a phone conversation, but wrote Davidson to say that his client was secretly taped, had never given consent to the video’s distribution, and was “distraught” over the Gawker leak.

The two lawyers spoke multiple times over the next few days. In subsequent sworn testimony and interviews with federal investigators, Houston said that Davidson described the Gawker leak as a “warning shot” fired by his clients. Houston claimed that Davidson made other “not so quite veiled threats.”

Davidson’s alleged “warning shot” comment was flagged by investigators, one law enforcement source told TSG, because it seemed indicative of “an intent to extort.” Davidson denies making the “warning shot” comment.

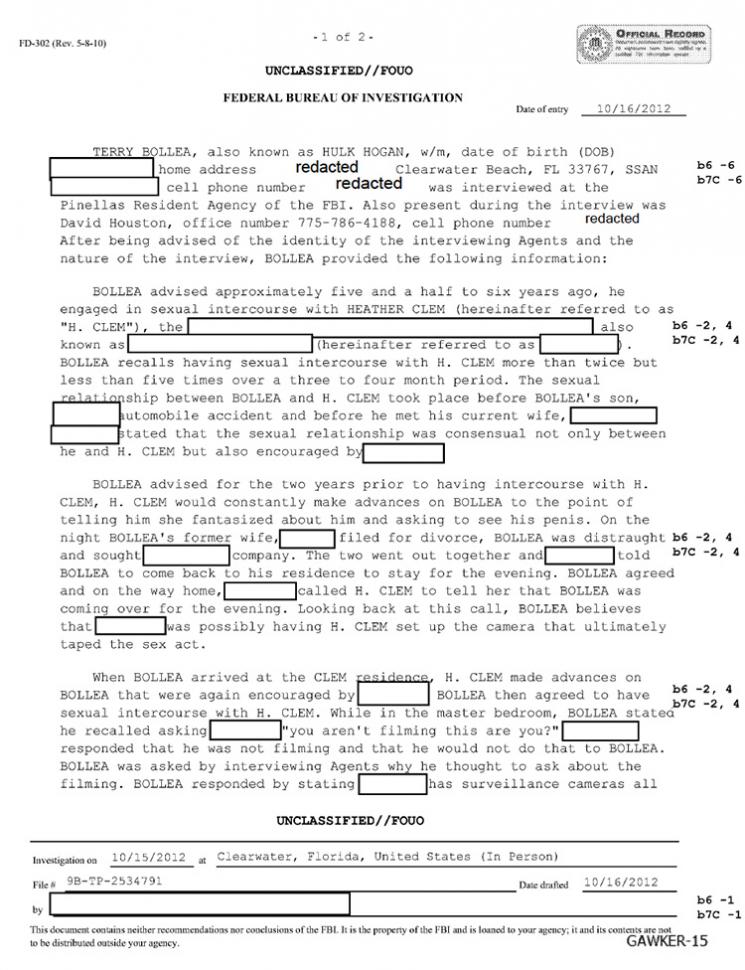

Five days after receiving Davidson’s initial e-mail, Hogan and Houston, whose office is in Reno, Nevada, traveled to the  FBI office in Clearwater, Florida. Hogan detailed his sexual encounters with Heather Clem and assured agents that the sex tape leak was not a publicity stunt. The wrestler said that he wanted “to prosecute whoever did this,” according to an FBI memo. Houston told agents about his contacts with Davidson. The Beverly Hills attorney, he said, “claimed that the possessors of the tapes obtained them legally as they purchased a laptop which contained said images/tapes.” Houston also said that Davidson told him that Hogan used racial epithets in one tape, and that if the video was released, it would damage the wrestler’s career.

FBI office in Clearwater, Florida. Hogan detailed his sexual encounters with Heather Clem and assured agents that the sex tape leak was not a publicity stunt. The wrestler said that he wanted “to prosecute whoever did this,” according to an FBI memo. Houston told agents about his contacts with Davidson. The Beverly Hills attorney, he said, “claimed that the possessors of the tapes obtained them legally as they purchased a laptop which contained said images/tapes.” Houston also said that Davidson told him that Hogan used racial epithets in one tape, and that if the video was released, it would damage the wrestler’s career.

On the same day that Hogan and Houston met with the FBI, the wrestler sued Gawker for $100 million, charging that the posting of the sex tape excerpt was an invasion of privacy that left him humiliated and stricken with severe emotional distress. It would emerge years later that Hogan’s massive legal bills were paid by Peter Thiel, the tech billionaire who for years nursed a grudge against Gawker, which he branded a “singularly terrible bully.”

It seems just as likely, however, that Hogan’s lawsuit was an attempt to halt any future release of the N-word video (by Gawker or any other outlet). Through conversations with Davidson--and apparently Walters, too--Houston and Hogan already knew of the damaging video’s existence. In an October 12 text to a friend, a concerned Hogan wrote  that “there’s more than one tape out there and a one that has several racial slurs we’re told.”

that “there’s more than one tape out there and a one that has several racial slurs we’re told.”

After consulting with a federal prosecutor, FBI agents opened an extortion investigation targeting Davidson (and his unknown clients) one day after Hogan and Houston filed their in-person complaint. Houston gave agents his e-mail correspondence with Davidson and agreed to record phone conversations with the California attorney. As he commenced cooperating with the FBI, Houston had no idea that Walters--a valuable source of information for Hogan's team--was responsible for connecting Davidson with Loyd, possessor of the sex tapes.

When asked about being played by Walters, Houston said he was shocked to subsequently learn that the TMZ employee was the “referral source between these goons and Davidson. It was pretty disappointing.” He added, “We have people actually referring clients, people that are media people. And I know they’re creating a story...that lubricates the wheel that runs their business. But, really?”

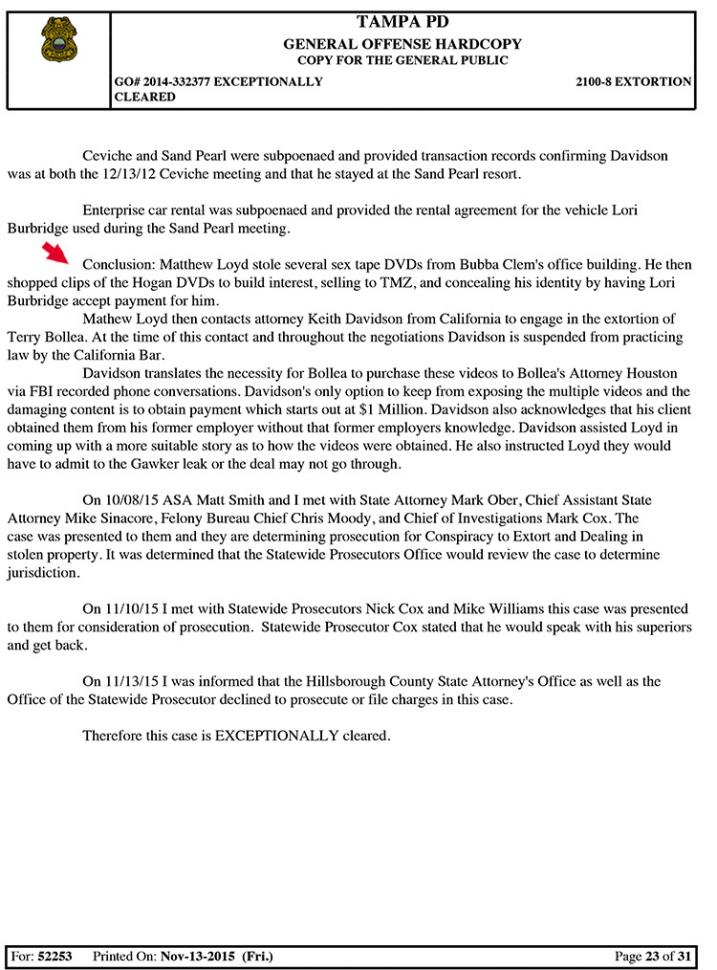

Documents from the FBI’s undercover investigation, a related state criminal probe, and the Gawker civil litigation paint a devastating portrait of Davidson as a lawyer who allegedly directed his clients to lie in an effort to facilitate a six-figure settlement from Hogan. Walters does not fare much better.

In a series of calls recorded over two months, some of which he placed from an FBI field office, Houston pretended to negotiate an actual settlement with Davidson. Transcripts of the calls provide a glimpse into Davidson’s approach in handling a deal for sex tapes, which he referred to as “the product” in one call. The transcripts also show Houston, who has practiced since 1978, trying to lead Davidson into making incriminating statements. But Davidson remained circumspect and issued none of the “veiled threats” that Houston attributed to him during their initial conversations (which were not taped).

![]()

Davidson told Houston, “I’ve been a fan of your client for years,” adding that Hogan “seems like just a really, really nice guy who was going through a really bad part in his life.” After declaring that, “I hope that you and I are dealing in a professional way that is truthful, open, candid,” Davidson told Houston it was “not my intention here to hold anybody over the fire...You know, I hope I’m part of the solution here.” At one point, Davidson even described one of Hogan's encounters with Heather Clem: “The sex is pretty straight. I mean...there’s nothing that would be even remotely unusual or fetish-like.”

In one recorded call, Davidson pushed Houston to commence monetary negotiations. “Alright then I’ll say a dollar,” Hogan’s lawyer said. Davidson, who chuckled at the opening offer, responded, “Well, I think that we would counter with, with a million dollars.” As the lawyers eventually hammered out the final details of a $300,000 settlement agreement, Davidson balked at certain language proposed by Houston, whose efforts negotiating the sham agreement were being overseen by the FBI. “You’re almost asking my client to admit that she’s an extortionist,” said Davidson. “My client puts, puts a signature on this, I think that’s an admission of criminal wrongdoing.”

During his conversations with Houston, Davidson said that his clients were responsible for providing Gawker with the leaked Hogan sex tape. This claim was crucial since it provided some assurance that the tapes being offered for sale were originals (and that copies had not been made).

It was also not true, according to Davidson’s clients.

With Loyd desiring anonymity, his friend Lori Burbridge--whom he previously used to receive the $8500 payment from TMZ--was set to act as the owner of the tapes. Burbridge, who faced financial problems and just had her car repossessed, agreed to be the straw seller in return for $10,000. Davidson’s plan called for Burbridge to accompany him to a future  settlement meeting with Hogan and Houston.

settlement meeting with Hogan and Houston.

During a conference call between Davidson, Loyd, and Burbridge, the subject of the Gawker leak was discussed. In an interview, Loyd recalled repeatedly telling Davidson that he had nothing to do with providing the tape to the web site. Davidson, he said, replied, “We have to admit it. You won’t be held responsible for anything.”

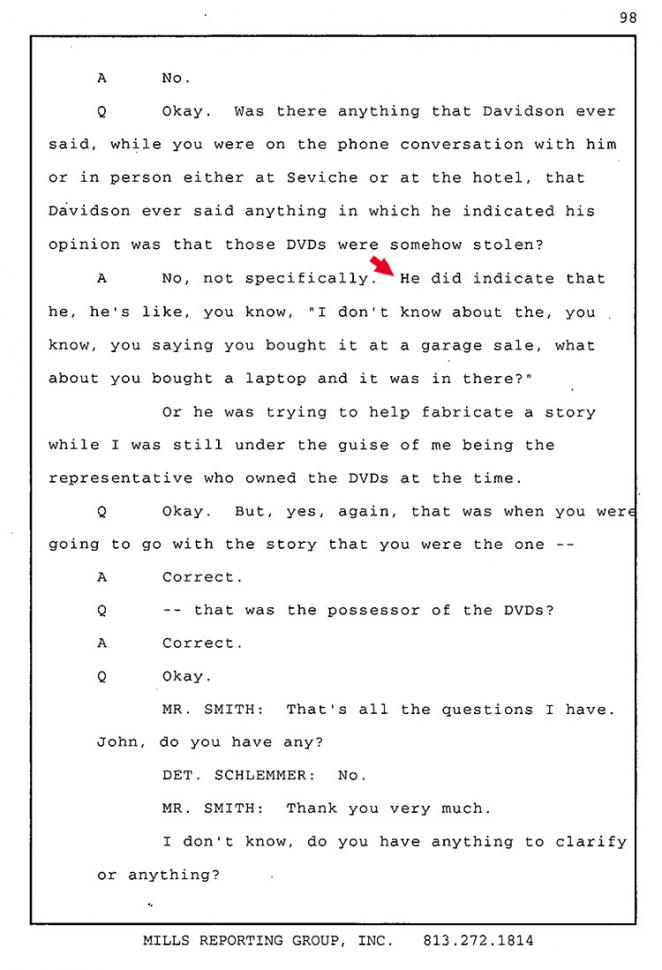

Burbridge, in an interview with state investigators, said that Davidson told her that, “I needed to say...that I was the one who sold the video to Gawker.” She added that Davidson “advised us explicitly that if we didn’t claim to have done that, to have sold to the Gawker, that the whole deal possibly wouldn’t go through.” If they did not claim responsibility for the leak, Burbridge told federal agents, “the sex tapes would lose their value.”

While later describing the conference call with Davidson to FBI agents, Burbridge said that she asked the lawyer if “the selling of the tapes was extortion.” Davidson, she said, replied that he had frequently done similar deals and that “the tapes were purchased and property that is purchased” can be legally resold. When an agent asked Burbridge why she thought to ask Davidson about extortion, she answered that the sex tapes “could hurt [Hogan] and they were trying to get [Hogan] to pay for it.” Burbridge, an FBI reports notes, “further stated that’s what she understood extortion to be.”

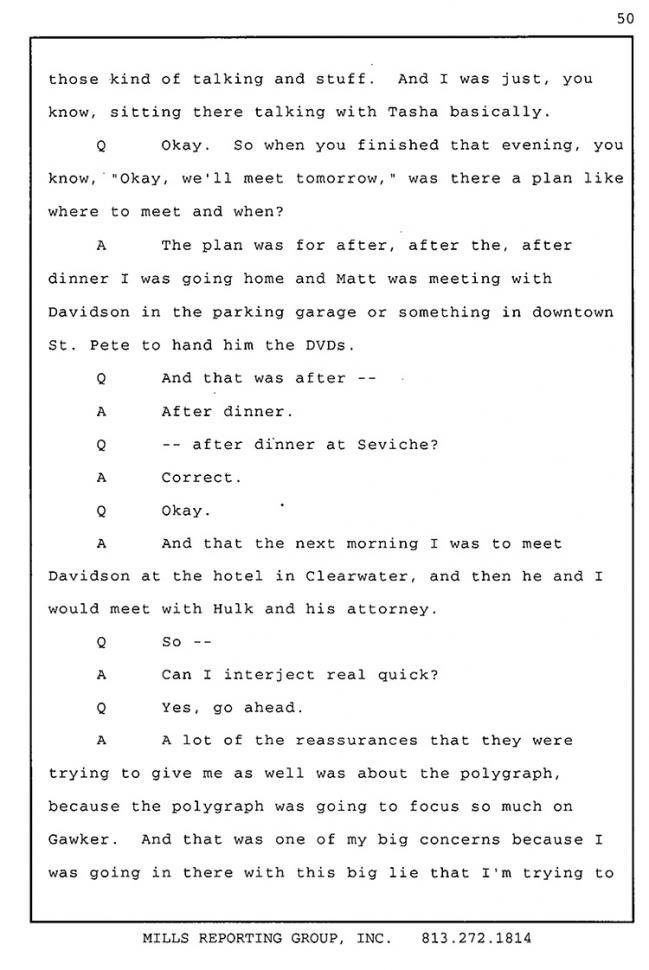

During the conference call, Davidson told Loyd and Burbridge that Hogan’s lawyer was demanding that Davidson’s client submit to a polygraph test on the day of the settlement meeting. Burbridge told the FBI that “Davidson knew Loyd did not release the material to Gawker and reassured everyone that the deal would still go through” even if she failed the polygraph. Burbridge told state investigators that she felt Davidson’s statement about the unimportance of the polygraph “came across as an overconfidence on his part.” The polygraph, Burbridge said, “was one of my big concerns because I was going in there with this big lie that I’m trying to pass as true that we were the ones that provided it to Gawker.”

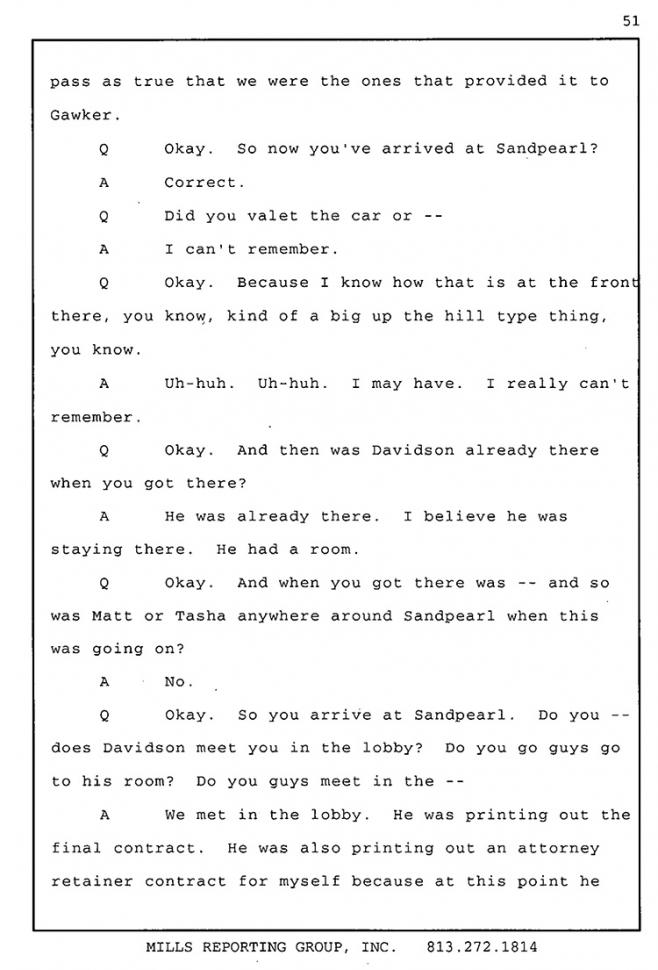

With a negotiated agreement in place, Houston and Davidson arranged to meet--along with their respective clients--at the Sandpearl Resort in Clearwater Beach to close the deal. Davidson, whose contingency fee arrangement called for him to receive 40 percent of the settlement ($120,000) plus expenses, arrived in Florida a day early so that he could meet his clients face-to-face for the first time. Davidson had no idea that a squad of FBI agents was already inside the hotel outfitting  Houston’s room with video cameras and listening devices. Or that those agents would be massed in an adjoining room monitoring his meeting with Hogan and Houston.

Houston’s room with video cameras and listening devices. Or that those agents would be massed in an adjoining room monitoring his meeting with Hogan and Houston.

The settlement agreement Davidson carried with him included the admission that his clients had provided Gawker with one of the sex tapes. The document was a template Davidson had used in other celebrity cases (and would employ in the Stormy Daniels matter). In earlier versions of the sex tape agreement Davidson shared with his clients and Houston, remnants from unrelated agreements remained in the document. Loyd recalled thinking, “This guy didn’t even customize a contract? He’s got a fucking template?”

During a dinner with Burbridge, Loyd, and Loyd’s wife, Davidson mentioned his various celebrity cases, saying he had just done a sex tape deal with Kanye West. At the end of the evening, Loyd gave Davidson the three Hogan DVDs. As part of the settlement agreement he had prepared, Davidson attached an exhibit describing the contents of the sex tapes in great detail. Writing like an overly enthusiastic blogger doing a TV recap, Davidson noted that Hogan could be seen lying in bed as Heather Clem “goes nuts giving oral.” On another tape, Davidson’s synopsis reported that Hogan was “breathing heavy Oh Fuck Im gonna cum oh fuck--suck my dick breathing heavy moans, orgasm.”

On the morning of the meeting with Hogan and Houston, Burbridge and Davidson had a prep session in his hotel room. Burbridge later told FBI agents Davidson reminded her of their phony claim about how the tapes were acquired: She “had bought a computer bag which contained the [Hogan] sex tapes.” Davidson, she recalled, said this in a “wink wink, nudge nudge” fashion. Burbridge described Davidson as “very adamant of trying to do everything to get the deal to go through,” which, she thought, was “so that he’d get his cut.” Burbridge told law enforcement officials that the lawyer had earlier said, “I don’t know about the, you know, you saying you bought it at a garage sale. What about you bought a  laptop and it was in there?” The location of where the DVDs were purportedly found fluctuated from on a laptop to inside a laptop bag.

laptop and it was in there?” The location of where the DVDs were purportedly found fluctuated from on a laptop to inside a laptop bag.

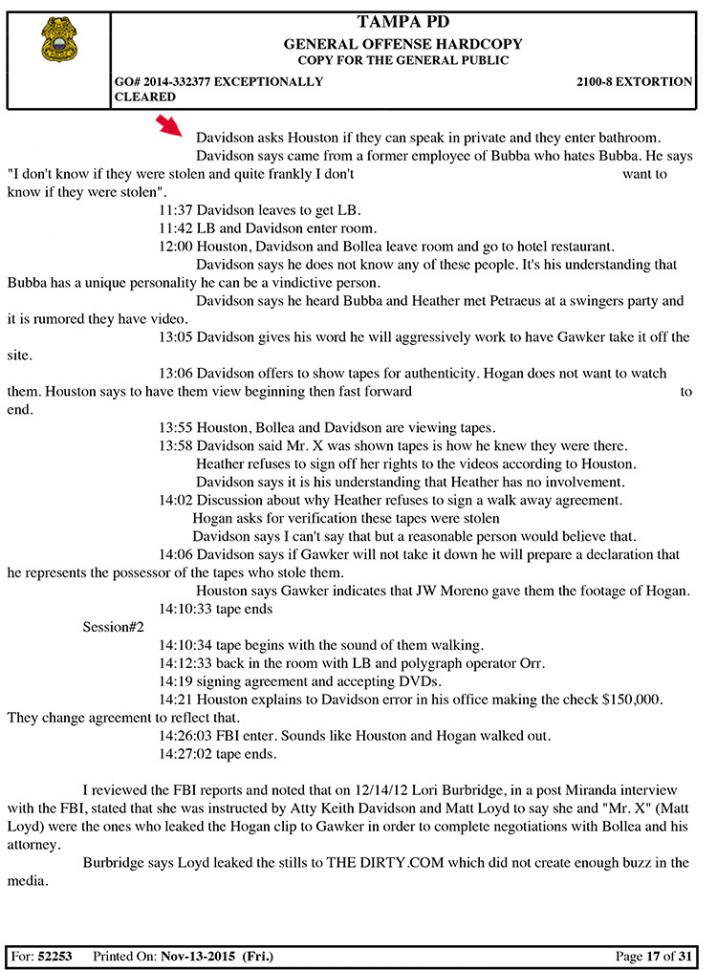

While Burbridge waited behind, Davidson arrived at Houston’s room at 11 AM. “It’s good to meet you. I’m sorry under these circumstances,” he told Hogan. “Yeah,” the wrestler responded. “At the end of the day...it’s our intent that these things go away, they go away forever,” Davidson then assured Hogan.

As the meeting progressed, Davidson again confirmed that his client was Gawker’s source. He also came under pressure from Houston to answer whether the tapes had been stolen from Clem. At that point, Davidson asked Houston if they could speak in private in the bathroom. Houston agreed. Inside the bathroom, Davidson admitted that the sex tapes came from a former employee of Clem who hated the shock jock. “I don’t know if they’re stolen,” said Davidson. “And, quite frankly, I don’t want to know if they were stolen.”

While Davidson made this admission out of earshot of a witness, Hogan, Houston was carrying an FBI recording device in his pocket. Perhaps Davidson should have turned on the faucets before declaring that he was unaware whether he was arranging the sale of stolen goods.

Davidson referred to the ex-Clem employee as “Mr. X.” and said that Burbridge was acting as the mystery man’s representative. After Davidson brought Burbridge into Houston’s room, she told Hogan that “Mr. X” was behind the Gawker leak. When Houston asked, “Why wasn’t the racial stuff released?” Burbridge answered, “The intent wasn’t to harm you...if that was released then what is it worth to you as well?” “Nothing,” Hogan replied.

According to an FBI report, Hogan and Houston then went to Davidson’s room to authenticate the sex tapes while Burbridge was questioned by a polygrapher (an ex-FBI agent who was aware of the sting operation). While viewing the tapes, Houston said, Davidson made a comment to the effect that, “The tapes that were released were the shot over the bow, but not the shot that would take the ship down.” A report by the polygrapher quoted Davidson saying he had previously handled 30 similar settlements, with only one “gone bad.”

That latter number was about to double.

The group moved on to signing multiple copies of the settlement agreement. Davidson handed over a silver case containing the three DVDs. And Houston gave Davidson a check for $150,000, the first of three installment payments. Then the front door and the door into the adjoining room opened and in flooded FBI agents. Hogan and Houston left, while Davidson and Burbridge were separated by agents.

Burbridge was bewildered and repeatedly asked whether she was "part of a hoax,” an FBI report notes. She also wondered whether the raid “was a bit” for Loyd’s radio show. After assuring her that the raiding party was composed of legitimate lawmen, an FBI agent read Burbridge her rights. She then agreed to cooperate with agents and began by saying that “the most important thing” the FBI needed to know was that she and Loyd “were not responsible for the Gawker sex tape leak.” That false claim, said Burbridge, was made “in order to complete the negotiations” with Hogan and Houston.

Davidson, who was not arrested, was accused of extortion by agents trying to spook the lawyer into answering questions. After being played some of the FBI’s surreptitious recordings, Davidson departed the hotel. Loyd, who was with his pregnant wife at a mall, learned of what occurred at the Sandpearl when he texted Davidson for an update. “FBI raided,” Davidson wrote. “You need to get an attorney.” Loyd replied, “You are my attorney.” “Conflict,” Davidson answered.

Davidson quickly hired Brian Albritton, a white collar defense lawyer who once served as United States Attorney for the judicial district that includes the Tampa-St. Pete area. Albritton would compile a 58-page presentation for federal prosecutors that described Davidson as an “ethical and trustworthy attorney” who negotiated a legitimate commercial deal with Hogan’s lawyer, a transaction that was absent “any threat or similar coercive inducement.”

Albritton also contended that a prosecution of Davidson might turn into a publicity vehicle for Clem and Hogan, both of whom would likely be called as government witnesses. Arguing that a criminal trial over the Hogan sex tapes would promote “Disrespect for Federal Law Enforcement,” Albritton concluded that the public would view “any such prosecution  as a waste of taxpayer dollars and wish a pox on both Hulk Hogan and Bubba the Love Sponge.”

as a waste of taxpayer dollars and wish a pox on both Hulk Hogan and Bubba the Love Sponge.”

For good measure, Albritton included a page detailing some of the shock jock’s more vile radio outrages. The page was headlined “Bubba brings the Circus--A History of Obscenity & Lies.” Albritton was unaware at the time that Clem’s untruths also included his claim during an FBI interview that Hogan was aware he was being recorded having sex with the shock jock’s wife. Clem was never charged for this lie to federal agents.

After seven months reviewing the evidence against Davidson, federal prosecutors decided not to file charges against the lawyer. The Department of Justice does not comment on what factors contribute to such declinations. Houston argued that government lawyers “had more than ample evidence” to prosecute Davidson. “That’s a conspiracy in anybody else’s county or district,” Hogan’s attorney declared. “For some reason Florida, I guess, that doesn’t amount to a conspiracy.”

Tampa police and state prosecutors would later examine the Hogan case, aided by the FBI’s recordings and other evidence. Matt Smith, a division chief with the State Attorney’s Office, was in favor of prosecuting Davidson and Loyd on conspiracy to commit extortion and dealing in stolen property charges. But while state investigators believed that a crime had been committed, they were not confident in the likelihood of conviction, said Smith, who was particularly concerned about the prospect of using Clem as a witness. He added, “A lot of jurors would be like, ‘Why the fuck do we care? Are you kidding me? We’re here because this guy’s fucking this guy’s wife on camera and didn’t know that he was getting filmed?’”

Albritton also met with state prosecutors and contended that a Davidson prosecution would stain the legal system. That pitch had little resonance, Smith said. The Florida prosecutor laughed, “We have stuff all the time that’s nonsense.”

Like their federal counterparts, Smith’s superiors ultimately declined to pursue criminal charges against Davidson.

* * *

It has been almost three years since Davidson walked away from the wreckage of the Hogan sex tape sting. But he remains shadowed by his activities in Florida.

In May 2016, two months after Hogan won a $140 million jury verdict against Gawker, the wrestler filed a lawsuit accusing Davidson, Loyd, Burbridge, and other defendants of extortion and invasion of privacy. Despite driving Gawker into the grave, Hogan was not done seeking retribution. He wanted to identify the source of a July 2015 National Enquirer story that disclosed the contents of the sex tape in which he made racist comments. The Enquirer story prompted World Wrestling Entertainment to immediately fire Hogan.

When TMZ reported that WWE was cutting ties with Hogan, its story included the “exclusive details” that “TMZ has seen the tape” on which Hogan “repeatedly used the n-word.” The site, of course, did not mention that it first saw the tape nearly three years earlier, but chose not to disclose its content. Amusingly, when TMZ founder Harvey Levin appeared at a tech conference in mid-2016, he was asked about the sex tape that sunk Gawker. “We were offered that tape, and we turned it down,” Levin claimed. “It wasn’t right for us. It felt  invasive to us.” The 67-year-old Levin apparently forgot about paying $8500 to “Spice Boy” Loyd for footage of Hogan having sex with Heather Clem.

invasive to us.” The 67-year-old Levin apparently forgot about paying $8500 to “Spice Boy” Loyd for footage of Hogan having sex with Heather Clem.

Davidson, representing himself in the Hogan II case, last month lost a motion to compel arbitration and stay the court proceedings. On March 23, he filed a five-page motion to dismiss Hogan’s lawsuit. Like the Hogan-Gawker lawsuit--during which Davidson was often referred to simply as “the extortionist”--the ongoing Hogan II case has been the source of more lumps for the L.A. attorney. During a recent hearing, Hogan lawyer Kenneth Turkel described Davidson as a “now disbarred lawyer” who was hired to “essentially shake down my client and extort him and threaten him.”

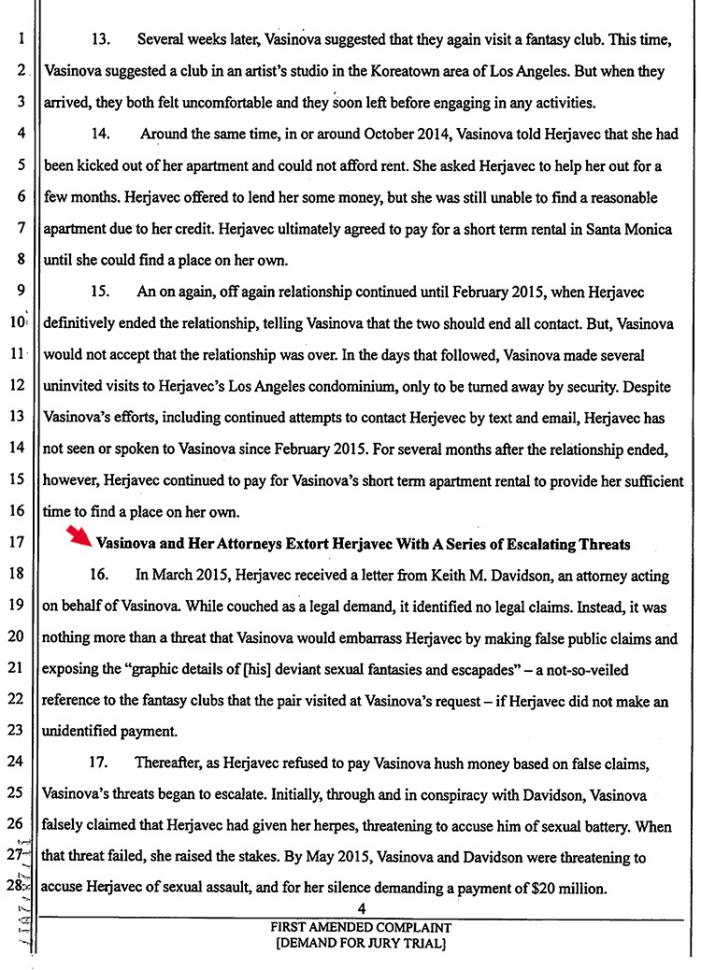

In addition to the Hogan litigation, Davidson is a defendant in two other civil matters accusing him of extortion: the action brought by the L.A. waiter who says he helped arrange the Pacquiao-Mayweather fight and a lawsuit filed in late-2017 by Robert Herjavec, one of the panelists on ABC’s “Shark Tank.” Herjavec, 55, alleges that Davidson conspired with Danielle Vasinova to try and secure a multimillion dollar hush money payment. Herjavec claims that Vasinova, a former girlfriend, and Davidson threatened to accuse him of sexually battering the 35-year-old woman and giving her herpes. Herjavec also reported receiving a legal demand letter from Davidson that threatened to expose the “graphic details” of the businessman’s “deviant sexual fantasies and escapades.”

If the Hogan II lawsuit survives Davidson’s dismissal motion, the lawyer will likely have to face a deposition by the wrestler’s legal team. This was an unpleasantness that Davidson was able to avoid in the Hogan-Gawker litigation. On the eve of trial, the web site’s attorneys sought to subpoena Davidson, an effort that his counsel fought off, in part by asserting the lawyer’s Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination.

But if Davidson had been compelled to answer questions under oath, he was prepared to object to one specific Gawker request. The lawyer did not want his deposition to be videotaped. Davidson considered the prospect of being filmed to be “unnecessary and meant merely to harass.” Also, he figured the tape would be leaked somewhere online.

- « first

- ‹ previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4