Al Sharpton's Secret Work As FBI Informant

Untold story of how activist once aided Mafia probes

View Document

Draft FBI Affidavit

-

Draft FBI Affidavit

-

Draft FBI Affidavit

-

Draft FBI Affidavit

-

Draft FBI Affidavit

-

Draft FBI Affidavit

-

Draft FBI Affidavit

Armed with Sharpton’s tapes and other fresh intelligence, the Genovese squad teamed with federal prosecutors to prepare a series of wiretap applications targeting “Chin” Gigante and his closest aides, including Venero “Benny Eggs” Mangano, Louis “Bobby” Manna, Dominick “Baldy Dom” Canterino, other made men, and crime family associates like Morris Levy.

Federal judges in New York City, New Jersey, and upstate New York subsequently granted permission for the wiretapping of numerous telephones and the placement of listening devices inside Genovese social clubs and a series of vehicles used by  Canterino to chauffeur Gigante. Each of those U.S. District Court applications included information gathered via Sharpton’s briefcase.

Canterino to chauffeur Gigante. Each of those U.S. District Court applications included information gathered via Sharpton’s briefcase.

But not every bugging attempt went smoothly.

The squad’s first attempt to wire Canterino’s auto ended disastrously. The Cadillac was parked in front of the hoodlum’s home when an FBI agent broke into the auto early one morning and drove off with the car (which was to be quickly returned to its spot after the listening device was planted). “Piece of cake,” the agent radioed to nearby surveillance agents as he drove away in Canterino’s ride. “You’re burned,” replied a panicked NYPD detective who spotted Canterino at the window of his Brooklyn house watching his vehicle get stolen.

“In retrospect, it was like a Keystone comedy,” laughed a former FBI agent who was on Canterino’s Gravesend block that day. “But it wasn’t so funny when it occurred.”

The Cadillac would later be destroyed in an arson fire, prompting the Genovese squad to seek judicial permission to bug Canterino’s new Dodge. The “probable cause” for the second application included material from Sharpton’s recordings. When it became clear that Canterino had switched to a third vehicle, another Cadillac, agents got permission to place a listening device in that car. Again, the court application relied, in part, on Sharpton’s taped conversations with Buonanno.

Canterino, an ex-longshoreman who had a forearm tattoo of an anchor with the word “Mom” inscribed within it, later told Genovese squad investigators he could not fathom how the bureau succeeded in bugging his car (albeit on the third try). Sitting in a Brooklyn diner with FBI agents Michael Ross and Ronald Parker  Pearson, Canterino said he “prided himself as being an excellent burglar, and it was his own anti-theft device which he had installed in the automobile,” according to an FBI interview report.

Pearson, Canterino said he “prided himself as being an excellent burglar, and it was his own anti-theft device which he had installed in the automobile,” according to an FBI interview report.

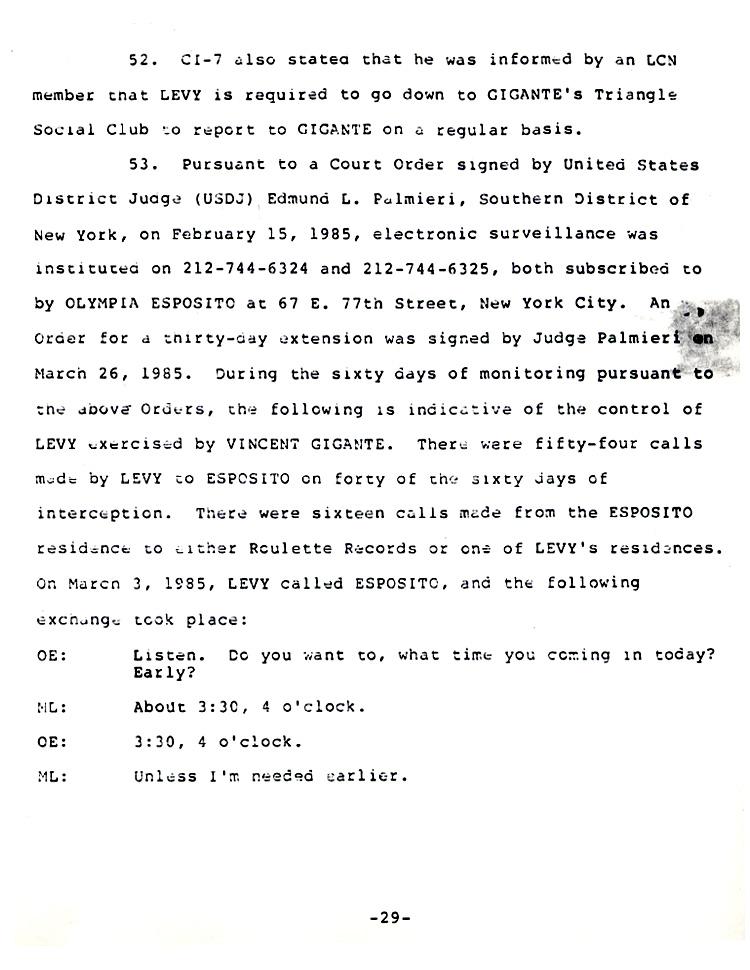

The Genovese squad also received court authorization to wiretap phones in Levy’s Manhattan office and his farm. Two lines in the Upper East Side residence of Gigante’s mistress were also bugged. That home, a townhouse between Park and Madison avenues, was purchased by Levy in 1981 for $520,000. Two years later, he sold the four-story property to Olympia Esposito, with whom Gigante had three children, for just $16,000. The Levy and Esposito wiretaps provided federal investigators with a detailed overview of how the businessman funneled millions in stock, cash, and other assets to Gigante’s paramour.

The section of the FBI wiretap affidavits containing the fruits of Sharpton’s cooperation was titled “The Extortion From and Control of Morris Levy.” The initial November 1984 affidavit, which had to be rewritten to further mask Sharpton’s identity, noted that the confidential informant had been providing information to the bureau for more than a year. The source learned of the information provided to investigators “through conversations with members of four of the LCN families in New York City, as well as in conversations with LCN members from other parts of the United States,” according to the affidavit.

As detailed in the various affidavits, the informant told FBI agents about Gigante’s control over Levy, how the mob associate was a “source of ready cash” for the Genovese gang, and that the only way Levy could escape the Mafia’s clutch was via his own death. The material placed in the affidavit was lifted directly from the bureau’s summaries of Sharpton’s meetings with Buonanno. While most of the FBI affidavits made it seem that “CI-7” was the primary source of information about Levy, Gigante, and Pagano, a latter court filing provided a more precise picture of how the informant operated. That  affidavit reported that the snitch was “advised by a member of an LCN family” about the Genovese family rackets.

affidavit reported that the snitch was “advised by a member of an LCN family” about the Genovese family rackets.

The electronic surveillance carried out by the Genovese squad eventually proved devastating to Levy, Canterino, and an assortment of wiseguys who would be convicted, in part, based on those surreptitious recordings (for which Sharpton helped establish the “probable cause”).

A month before Levy’s arrest on federal extortion charges, a pair of FBI agents went to his Roulette Records office to serve a grand jury subpoena for business records. While there, the investigators told Levy he had been the subject of electronic surveillance in the course of the Genovese squad probe. According to an FBI report memorializing the encounter, the agents told Levy that his life “may be in jeopardy due to the implication of Olympia Esposito and Vincent ‘Chin’ Gigante in the criminal investigation stemming from the activities of Levy.”

Levy, though, made it clear that “flipping” was not in his future. Remarking that he knew what the “rules” were, Levy told agents William Confrey and Stephen Steinhauser that he had dealt with wiseguys for 40 years and “held no fear for his safety based on these relationships.” When the agents replied that he had a choice if he felt threatened, Levy said that, “the witness security program was a joke and could not adequately protect witnesses.”

At the subsequent trial of Levy and Canterino, defense lawyers argued that the judge should direct prosecutors to identify several of the confidential FBI sources cited in wiretap affidavits. That request was denied after a Justice Department prosecutor responded that such a disclosure could result in the murder of the informants.

Defense motions specifically referred to information provided to the bureau by informants dubbed “CI-7” and “CI-8” in FBI documents. What the lawyers for Levy and his codefendants did not realize, however, was that “CI-7” and “CI-8” were the same person--Sharpton. Due to a numbering switch, the reverend was referred to as “CI-8” in the narrative of some of the FBI affidavits. Defense counsel was not apprised by prosecutors that a single FBI informant had been identified with two separate “C-I” numbers.

Levy was subsequently convicted of two felony counts and sentenced to a decade in prison, while Canterino got a dozen years. In pre-sentencing letters to the judge, Quincy Jones, Willie Nelson, Dizzy Gillespie, Tito Puente, and assorted record  label executives saluted Levy’s charity and loyalty.

label executives saluted Levy’s charity and loyalty.

While free on appeal, Levy died of cancer in May 1990 at his upstate New York home. Canterino, who had survived quadruple bypass surgery, died several years later while in Bureau of Prisons custody, a less bucolic departure point than Levy’s beloved Sunnyview Farm.

With Sharpton’s help, the Genovese squad also secured a wiretap on the home phones of Federico “Fritzy” Giovanelli, a family soldier often seen at Gigante’s Sullivan Street social club, and two of the Queens wiseguy’s associates. Tapes from those bugs were subsequently used to help convict Giovanelli, Steven Maltese, and Carmine Gualtiere of a racketeering conspiracy that included the murder of Anthony Venditti, an NYPD detective assigned to the Genovese squad. Each of the men was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison, though the portion of the verdict dealing with the Venditti killing was subsequently vacated on appeal.

The 34-year-old Venditti, a married father of four young daughters, was shot to death in January 1986 while he and a partner were surveilling Giovanelli. The Genovese soldier was tried three separate times on state murder charges. The first two trials ended in hung juries, while the third case, brought after the federal appeals ruling, resulted in Giovanelli’s acquittal.

Genovese squad agents were actually monitoring Giovanelli’s phone on the evening of Venditti’s murder. They listened as his wife Carol dialed Maltese at 10:57 and yelled, “It’s all over TV. My kids are going crazy. He shot a cop!” She added, “Freddy shot a cop!” In the call’s background, sobbing can be heard. Later that evening, Giovanelli called home while in  police custody and tried to calm his spouse. “Babe,” he said, “you know that’s not my style.”

police custody and tried to calm his spouse. “Babe,” he said, “you know that’s not my style.”

During a conversation last month, Giovanelli said that the FBI bug resulted in “5000 hours of me speaking with my friends about cooking” and other innocuous topics (which, to some degree, is true). Unaware of Sharpton’s work as an FBI informant, Giovanelli said that he thought the main reason his phone calls were intercepted was “because somebody got a broken jaw,” a reference to a record distributor who had run afoul of Levy & Co. and, as a result, got beaten by Gaetano “Corky” Vastola, a member of the New Jersey-based DeCavalcante crime family. The victim, who was being extorted by a coterie of hoodlums, cooperated with the FBI and entered the Witness Security Program.

The gravelly-voiced Giovanelli, who has survived a couple of aneurysms and heart valve replacement surgery, suggested that a reporter look at “the good side” of Sharpton instead of plumbing the reverend’s past. “I feel sorry for him,” Giovanelli laughed. “Here’s a guy who lost a hundred pounds and along comes a Bastone wielding a bastone to ruin things.” In Italian, a “bastone” is a wooden cane.

While Joseph and Daniel Pagano were not primary targets of the Genovese squad, the father-son combo was the focus of a parallel probe being conducted by investigators with the New York State Attorney General’s Office. And like their federal counterparts, the AG’s Organized Crime Task Force (OCTF) would also benefit from Sharpton’s work as an informant.

Like the Genovese squad, state OCTF agents believed that listening devices would produce incriminating evidence against the Paganos and members of their Genovese crew. According to investigators with both task forces, a close relationship existed between the groups--so much so that several Genovese squad members ended up working for the state task force,  which was headquartered in Westchester County, a Pagano stronghold.

which was headquartered in Westchester County, a Pagano stronghold.

When the state OCTF sought court approval in January 1986 to place a listening device in Joseph Pagano’s Rockland County home, they cited a confidential FBI source who told his handlers that the mafioso conducted business in the basement of the Monsey house. In interviews, Genovese squad and state OCTF investigators identified Sharpton as the informant who provided a first-hand description of Pagano’s residence.

As expected, that listening device--and several other OCTF bugs--generated a wealth of evidence against the Pagano crew. Joseph was overheard reminiscing about the days when he moved kilos of heroin with Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno, a fellow son of East Harlem who preceded “Chin” Gigante as Genovese family boss. Pagano was also recorded giving a succinct analysis of his son Daniel’s executive limitations: “He’s an opener, not a closer,” Pagano said.

The OCTF investigation, which spanned more than two years, ended in June 1989 with the indictment of five Genovese crime family figures on enterprise corruption charges. But only the younger Pagano ended up in the dock. His father, who had been seriously ill during the course of the OCTF probe, died two months before a grand jury accused his son and other underlings of engaging in mob staples like loan sharking, extortion, and gambling.

Each defendant subsequently pleaded guilty to various criminal charges, so there was no public presentation of evidence against the men. Which meant that OCTF prosecutors did not have to further expound on the indictment’s allegation that Daniel Pagano “solicited the use of a bank account of the National Youth Movement” to launder money.

Sharpton, who controlled that bank account, was not charged in connection with the Pagano investigation.

* * *

According to Sharpton’s most recent book, following the “Victory Tour,” King “decided that I should become a major concert promoter, working alongside him to become to the music industry what he was to the boxing world.” Sharpton--who formed a Georgia-based company, Hit Bound, Inc., to handle music promotions--wrote that he was also being urged by Michael  Jackson and James Brown to enter the concert business.

Jackson and James Brown to enter the concert business.

But, Sharpton declared, he opted for the more “uncertain path” of civil rights activism, eschewing the prospect of “big stacks of dollars that could be very helpful in raising a family.”

Sharpton’s unique brand of activism included working with Curington to line up the endorsements of several prominent black ministers for Senator Al D’Amato, the conservative Republican incumbent then being challenged in the 1986 general election by liberal Democrat Mark Green. The ministers backing D’Amato included Bishop Frederick Douglas Washington, whom Sharpton has described as one of his spiritual mentors. The endorsements came several months after the The New Republic reported that D’Amato had privately referred to the residents of public housing projects as “animals.”

In return for the endorsements, D’Amato--who was easily reelected--steered a $500,000 federal grant to Curington and Sharpton for the establishment of an anti-drug program in Brooklyn. According to a grant application, Curington, whose prior narcotics experience landed him on a DEA list of “Class 1” traffickers, was slated to serve as the program’s executive director. Sharpton and Curington, the application noted, also planned to secure an additional $750,000 in “corporate support” from eight record labels.

The duo’s plan foundered, however, when officials at a Brooklyn church changed their mind about allowing a drug treatment facility to operate from a church building. As a result, the $500,000 grant was later canceled.

At D’Amato’s request, Sharpton also arranged for Coretta Scott King to make a surprise appearance at the August 1988 Republican National Convention in New Orleans, according to a law enforcement official. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s widow, who Sharpton has called “my mentor,” sat in Vice President George Bush’s box, where she was greeted with a kiss by Barbara Bush.

Sharpton apparently forgot about the six-figure D’Amato handout when he was penning his latest book. Claiming that his public positions were free of unseemly calculations, he claimed, “I never asked for public funding for anything, so there  would be no confusion about my motives.”

would be no confusion about my motives.”

By the time Sharpton’s “uncertain path” led him to join the Tawana Brawley team in mid-December 1987--when he demanded the arrest of the "racial beasts who are terrorizing the state"--his four-year-long cooperation with law enforcement agencies had almost run its course.

It had been five months since ex-FBI Agent Joe Spinelli steered him to the Los Angeles federal prosecutor who had to position himself at a pay phone when Sharpton was ready to drop a dime. And Sharpton’s work on behalf of the Brooklyn U.S. Attorney’s Office--also at Spinelli’s urging--was snuffed out in its infancy in January 1988.

But while the Brawley affair left Sharpton radioactive for law enforcement, the same could not be said for his underworld contacts.

Beginning in late-1987 and carrying through the following year, Sharpton and Curington worked together on behalf of Sugar Hill Records to broker a multimillion dollar deal with MCA Records in Los Angeles. In an interview, Curington valued the contract at $6.5 million, adding that he and Sharpton stood to split a hefty six-figure fee for arranging the deal with MCA  chairman Irving Azoff.

chairman Irving Azoff.

Sugar Hill was founded by Joe Robinson, a music industry veteran who, strapped for cash, took money from Morris Levy in return for a piece of the fledgling rap/R&B label. Like Levy and many of his peers in the rough-and-tumble record business, Robinson was unburdened by business ethics. “He was as greasy as a pork chop,” said Curington.

The Sugar Hill-MCA deal eventually collapsed amid claims that Robinson had engaged in various financial malefactions. Which, of course, did not relieve the Sugar Hill boss of his financial obligation to Curington and Sharpton. At least that was how the duo saw it.

Enveloped in debt and hurting for cash, Robinson nonetheless began getting a stream of unannounced visitors at Sugar Hill’s Englewood, New Jersey studio demanding that he pay Sharpton and Curington. On one occasion, “Joe Bana” Buonanno showed up with Genovese associate Mike Milano and confronted Robinson, who called a local cop to complain that he was being muscled by the men. Edward Stempinski, then an Englewood Police Department detective, recalled catching Buonanno and Milano at Sugar Hill, remarking that the duo “didn’t look like they should be going into a rapper’s studio.”

During a trip to Englewood, Curington was busted after punching one of Robinson’s sons. Stempinski, now retired, said that in a post-arrest interview, Curington identified himself as vice president of Sharpton’s National Youth Movement.  Sharpton, who was then living in Englewood with his wife and two young daughters, also took part in the debt collection effort, visiting Sugar Hill to hector Robinson about payment, said Stempinski.

Sharpton, who was then living in Englewood with his wife and two young daughters, also took part in the debt collection effort, visiting Sugar Hill to hector Robinson about payment, said Stempinski.

Referring to Joe Robinson, Curington admitted, in a TSG interview, to threatening the Sugar Hill boss over the money owed to him and Sharpton, adding that he warned Robinson that he would burn down Sugar Hill’s headquarters if they were not paid. Curington also admitted that he once went to Sugar Hill intending to “fuck up” Robinson, though he did not arrive solo. Curington said he was accompanied to the studio by Buonanno, “Wassel” DeNoia, and Daniel Pagano.

In an interview in his Manhattan apartment, DeNoia said that he could not recall traveling to the Sugar Hill studios to lean on Robinson. Now 88, time and illness have stripped the hulking former bookmaker of his menace, though not his affection for Sharpton and Joseph Pagano, a close friend since their youth in East Harlem. DeNoia called Sharpton a “really dear friend of mine,” saying that they met when Sharpton handled music promotions. He recalled  that Sharpton became “very close” to his boyhood friend, adding that the activist “loved Joe Pagano.”

that Sharpton became “very close” to his boyhood friend, adding that the activist “loved Joe Pagano.”

Stempinski, who shared details of the hoodlum caravan going westbound over the George Washington Bridge with several organized crime investigators, was surprised to discover that Sharpton had apparently learned of law enforcement’s monitoring of the Sugar Hill matter.

The detective arrived at work one day to find a remarkable two-page letter had been mailed to him by Sharpton, who was then eight months into his defense of Tawana Brawley.

Stempinski--who had never met or spoken with the activist--concluded that Sharpton sent the out-of-the-blue missive to him at the direction of Curington, whom Stempinski had been cultivating as a source. Curington, Stempinski recalled, “dropped dimes” on Sharpton, including a heads-up that the reverend was helping D’Amato orchestrate Coretta Scott King’s appearance at the 1988 Republican National Convention.

The August 23, 1988 correspondence stated that Sharpton and Curington had been retained as “consultants” by Robinson, who thought he was “being unduly and unfairly treated for racial reasons” by MCA. The pair was hired, Sharpton wrote, due to their MCA contacts and “standing in the black music community.” Sharpton then recounted Curington’s immersion in the Sugar Hill-MCA deal, a diligence which came at the expense of other “private business” and “community efforts” with which the duo was involved.

After noting that Robinson had leveled accusations of abuse against Curington, Sharpton dismissed those claims as false, stating that the Sugar Hill owner “fabricated” the allegations with the “intent of not meeting his obligations to me or Mr. Currington.” Sharpton declared that he would not tolerate “our movement, friends, co-workers, and associates to be prostituted and mis-used in this manner.”

Sharpton’s letter to the Englewood detective concluded with the promise that, “I can assure you I am prepared to move  legally and publically (marches, press conferences) to get my money, Mr. Currington’s money, and the movement’s money. I hope these activities will be solved soon.”

legally and publically (marches, press conferences) to get my money, Mr. Currington’s money, and the movement’s money. I hope these activities will be solved soon.”

Sharpton’s aggressive, preemptive strike made his position clear: He and Curington were victims of Robinson’s perfidy. And if anyone doubted that, they should prepare to endure the raucous Brawley-type protests for which Sharpton was becoming notorious.

As for menacing guys showing up at Sugar Hill’s studio, well, Sharpton's letter did not address the sticky subject of all those Italian-American debt collectors, a group that included Buonanno, the mafioso who, years earlier, had been secretly taped by “CI-7.”

Sharpton told TSG that he could not recall writing to the New Jersey detective. Asked why an assortment of wiseguys would have been pressuring Robinson to pay a debt owed to him and Curington, Sharpton replied, “What makes you think I knew about that?”

***

Two years before signing with MSNBC in 2011, Al Sharpton traveled to Los Angeles to try and sell a daytime TV show that would have starred him in a “Judge Judy”-type role. His partner in the “Judge Sharpton” endeavor was James Rosemond, a music industry executive who paid airfare, hotel, and other expenses related to the proposal (which did not ultimately  secure a Hollywood green light).

secure a Hollywood green light).

Like many of Sharpton’s prior business acquaintances, Rosemond, too, had a nickname: “Jimmy Henchman.”

At the time of the “Judge Sharpton” pitch, Rosemond, who managed hip-hop artists, already possessed a lengthy rap sheet and had served nearly seven years in prison for various weapons and narcotics convictions. He also happened to head a large bi-coastal cocaine trafficking ring. The notorious drug kingpin is now serving life in prison for that criminal operation, proceeds from which Rosemond used to cover “Judge Sharpton” costs.

In recent months, as Sharpton has been promoting his latest book, interviewers have not bothered to ask about Rosemond or any other gangsters to whom the civil rights leader has been linked.

Instead, Oprah Winfrey, Wendy Williams, Matt Lauer, and others have focused on Sharpton’s trim figure, his growing political influence, and Brawley, the albatross that hangs around his neck like Flavor Flav’s clock. Viewers of these Q&A sessions learned that daily cardio workouts and a healthy diet (no meat, two pieces of whole wheat toast for breakfast, and no food after 6 PM) can help a guy shed 54.8 percent of his body weight.

When he was last profiled on “60 Minutes,” Sharpton--“stately in his tailored suits”--was filmed inside the private Manhattan  cigar club he frequents, as well as at a Sunday church pulpit. “I like folk that been knocked down and shamed and disgraced and somehow God picked them up and cleaned them off and brought ‘em back,” he told the cheering congregation.

cigar club he frequents, as well as at a Sunday church pulpit. “I like folk that been knocked down and shamed and disgraced and somehow God picked them up and cleaned them off and brought ‘em back,” he told the cheering congregation.

Near the conclusion of the 12-minute piece, correspondent Lesley Stahl introduced investigative reporter Wayne Barrett, who began covering Sharpton’s exploits more than 30 years earlier, when the activist was involved in Brooklyn political campaigns. Sharpton, Barrett said, was “in the civil rights business. I don’t think he’s a civil rights leader.”

Barrett then wondered, considering Sharpton’s tawdry history, “Would anybody else be able to transcend that and be this larger than life figure?”

“He has,” Stahl chirped.

“Only because we let him,” replied Barrett.

- « first

- ‹ previous

- 1

- 2

- 3