Trump Limos Were Built With A Hood Ornament

Developer's first licensing deal was with mafioso

View Document

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

-

John Staluppi Docs

SEPTEMBER 22--Long before consumers could purchase Donald Trump-branded steaks, chocolate, water, ties, suits, wallets, cufflinks, dress shirts, vodka, watches, eyewear, and cologne, there was the Donald Trump signature series Cadillac limousine.

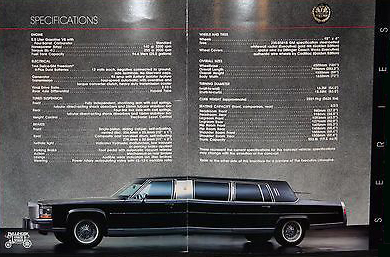

Introduced in 1988, the Trump Golden Series and Trump Executive Series models were sumptuous, rosewood-paneled offices on wheels--and the developer’s first foray into licensing  his name.

his name.

During an unveiling at a limousine trade show in Atlantic City, Trump was characteristically reserved. “You can see the kind of quality there is. We left nothing out. I’m very honored that they built me the first one and, frankly, I deserve it,” he said.

The Trump limos offered Italian leather upholstery, wool carpeting, a TV and VCR, a fax machine, a paper shredder, and pop-out writing desks. A cabinet even contained stemware and a Perm-a-Pub push-button liquor dispenser. The stereo system was a Blaupunkt, the two cell phones were from NEC, and the Golden Series model had gold-plated Vogue tires.

And as for the hood ornament, he was a product of the Colombo organized crime family.

The Trump limousines were built by Dillinger Coach Works, a New York firm run by partners John Staluppi and Jack Schwartz. The men were auto industry veterans and each was a convicted felon at the time of the Trump unveiling. Staluppi’s rap sheet included an early-70s conviction for stealing auto parts, while in 1976 a federal jury found Schwartz guilty of extortion. At Dillinger--which was named after the Depression-era gangster--Staluppi oversaw production, while Schwartz headed sales.

When Trump was gifted the first stretch limo bearing his name, the businessman told trade show attendees that the vehicle’s development began two years earlier when he ran into a General Motors official in Palm Beach, Florida. Trump recalled suggesting that, “Cadillac ought to come up with a design for an incredible limousine that has the big headroom and all of the assets that anyone could  want.”

want.”

The developer said that he subsequently agreed to help design the Trump limousines, but admitted, “I know nothing about cars except what I personally like. But between myself, Cadillac, and John Staluppi at Dillinger... we went ahead and designed the car.” Team Trump went back and forth on a prototype before settling on the final product. “And we think we probably designed the ultimate limousine to be found anywhere in the world,” Trump declared.

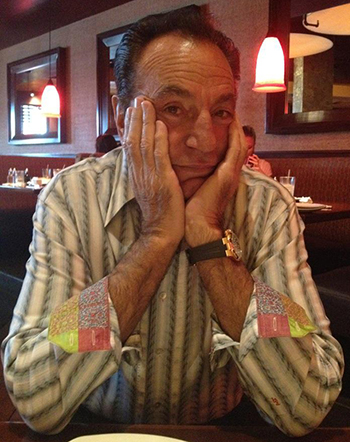

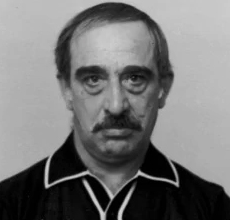

But while Trump saluted him at the Atlantic City event, the mobbed-up Staluppi, seen above, stayed in the wings with Schwartz. Instead, the partners had an underling appear on stage with Trump and a GM official, recalled Schwartz, who said the nominee was Dillinger’s president “in name only.” The Dillinger representative was drafted into service, Schwartz said, due to the “unfortunate” criminal entanglements of the company’s principals. Schwartz, 86, recalled that Dillinger’s designated front man “was a nervous wreck when they put the mic in front of him.”

When Trump signed the deal with Dillinger, he was fast becoming a household name. His first book, “The Art of the Deal,” was five months into a year-long stay on the New York Times best seller list, and construction was underway on his third casino in Atlantic City, where the gambling industry was booming.

Trump’s March 1988 contract with Staluppi & Co. granted the licensee a “limited exclusive right to fabricate, advertise, market, promote and sell” the Trump limousine in the United States. As part of the two-year deal, Schwartz said, Trump agreed to purchase about 20 of the vehicles for use at his Atlantic City casinos. [A series of photos showing a 1988 Trump limo--now owned by a British car collector--can be seen here.]

Since Trump’s vetting of the Dillinger deal surely included the industry’s most terrific, incredible, and luxurious due diligence, the developer apparently had no problem licensing his name to Staluppi, whose Mafia bona fides had long been established by law enforcement officials.

In 1981, four years before Trump opened his first casino, he met with a pair of FBI agents to “express his reservations about building a casino in Atlantic City,” according to an FBI memo. Trump told investigators that he “read in the press media and had heard from various acquaintances that Organized Crime elements were known to operate in Atlantic City.” Trump added that he wanted to build a casino, but “did not wish to tarnish his family’s name.” In a follow-up meeting, Trump told an FBI agent that he wanted to provide “full disclosure” during the construction of his casino, and even “suggested that [the FBI] use undercover Agents within the casino.”

Trump’s supposed qualms about dealing with Atlantic City’s wiseguy element had subsided enough by 1982 that the developer paid Philadelphia mobster Salvatore Testa twice market rate for a piece of property that became part of a larger assemblage upon which the Trump Plaza casino was built. Additionally, as journalist Wayne Barrett reported in his investigative biography of Trump, the developer used a pair of construction companies controlled by leaders of Philadelphia’s mob family to help build his inaugural gambling den.

By the time Staluppi, now 67, went into business with Trump, the Brooklyn native had been the subject of several law enforcement investigations, including an undercover operation run by Long Island prosecutors probing his ties to the leadership of the Colombo crime family, one of New York’s five Mafia outfits.

During that Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office investigation, an undercover cop worked as a chauffeur for Staluppi, a 10th grade dropout who was already a multimillionaire through his ownership of car dealerships in Brooklyn, Queens, and Long Island.  However, when he tried to expand into the Manhattan nightclub scene, the State Liquor Authority rejected Staluppi’s application for a liquor license due to his rap sheet (as well as the criminal records of his business associates).

However, when he tried to expand into the Manhattan nightclub scene, the State Liquor Authority rejected Staluppi’s application for a liquor license due to his rap sheet (as well as the criminal records of his business associates).

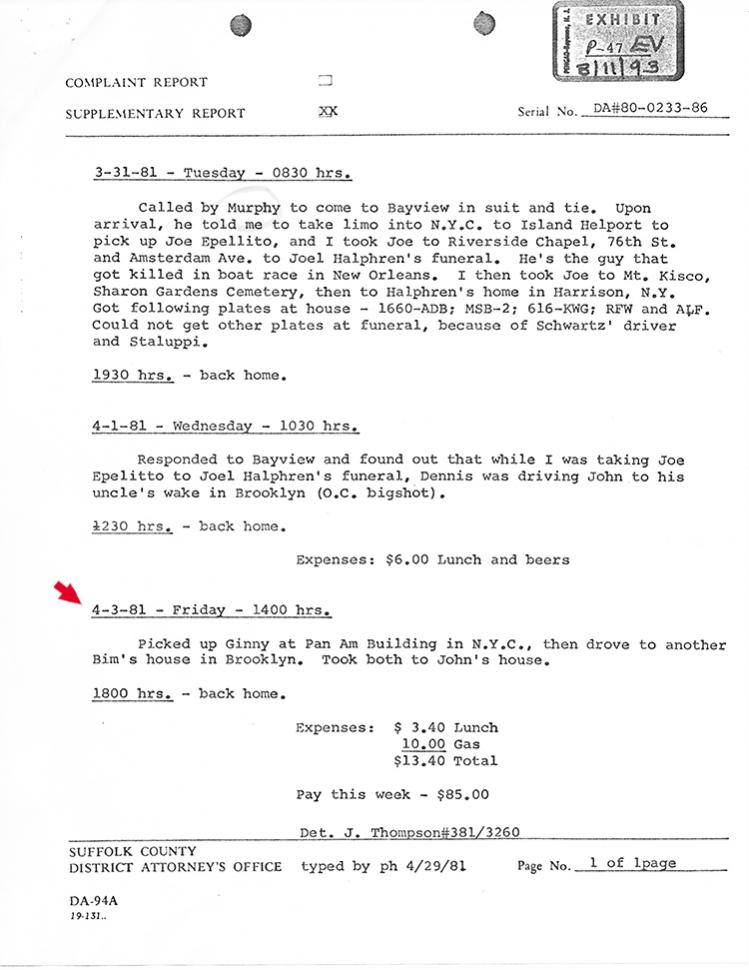

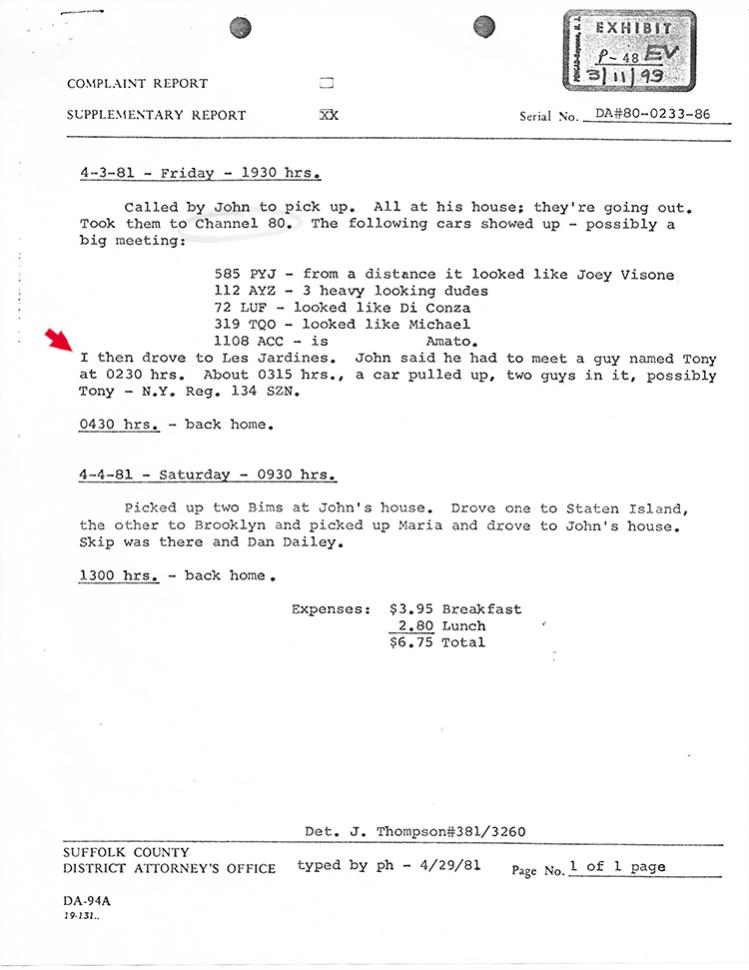

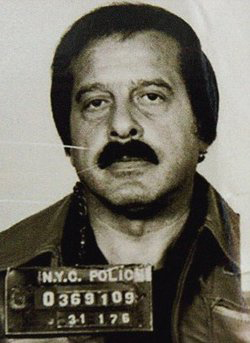

In a series of investigative memos, the undercover cop detailed Staluppi’s meetings with Colombo crime family figures during 1980 and 1981. The undercover reported that Staluppi met at least twice with family boss Carmine “The Snake” Persico at a Brooklyn auto dealership. The cop noted that Staluppi also socialized with Colombo soldiers Pasquale Amato, who owned an auto wrecking firm, and John Rosatti, with whom Staluppi owned auto dealerships. The undercover also reported that Colombo captains Sebastian Aloi and Frank Fusco attended a Staluppi/Rosatti Christmas party at which the ranking gangsters “were treated as if they were honored guests.” Rosatti is pictured below.

The undercover cop was also dispatched to pick up and drop off a rotating group of Staluppi girlfriends. On one Friday afternoon, the cop reported, he “Picked up Ginny at Pan Am Building in N.Y.C., then drove to another Bim’s house in Brooklyn. Took both to John’s house.” “Bim” appears to be short for “bimbo.”

Following one Saturday dinner and a trip to a Long Island nightclub, a friend suggested that the Staluppi party cap the evening with a visit to a disco that was secretly owned by Colombo soldier Michael Franzese. Staluppi, the undercover  noted, shot down the idea, saying that law enforcement agents were at the nightspot “taking plate numbers.” Months later, the cop drove Staluppi to the Franzese disco--which hosted several high-level Colombo family sitdowns--after “John said he had to meet a guy named Tony” at 2:30 AM.

noted, shot down the idea, saying that law enforcement agents were at the nightspot “taking plate numbers.” Months later, the cop drove Staluppi to the Franzese disco--which hosted several high-level Colombo family sitdowns--after “John said he had to meet a guy named Tony” at 2:30 AM.

Staluppi’s Mafia connections were first examined in Atlantic City in 1984, during the course of a Division of Gaming Enforcement (DGE) investigation into Schwartz, who was seeking to have his auto leasing business licensed as a casino vendor.

According to state records, a DGE investigator reported that Staluppi had a criminal record and was associated with Colombo crime family members. A 1984 DGE report noted that, “He (Staluppi) is now under investigation by the Organized Crime force on Long Island.”

In a sworn DGE interview, Schwartz said that he was “aware of Staluppi’s connection to organized crime, but is skeptical as to the alleged association.” By his own admission, Schwartz was no stranger to wiseguys. In both an interview and his self-published book, Schwartz referred to former Colombo boss Joseph Profaci as his “replacement father,” and called Henry “Chubby” Bono, a Bonanno crime family soldier, a “dear friend” whom he considered part of his family. Additionally, Schwartz’s phone book, a DGE report noted, included contact information for a Gambino crime family captain, Colombo soldier John Pate, and a used car lot operated by a Luchese family member (who was eventually rubbed out inside the Brooklyn business)

Schwartz’s extortion conviction stemmed from his attempt to secure money from a debtor. After his collection efforts were repeatedly rebuffed, an “incensed” Schwartz “contacted some friends from my past life with” Profaci and asked them to “pay [the debtor] a visit.”  Though Schwartz (seen at left) contends in his book that he “clearly stated that no violence was to be used,” the victim was threatened by the debt collectors, who also set fire to the man’s garage and automobile.

Though Schwartz (seen at left) contends in his book that he “clearly stated that no violence was to be used,” the victim was threatened by the debt collectors, who also set fire to the man’s garage and automobile.

Schwartz, a reformed rake who just turned 86, told TSG that Staluppi was a “mechanical genius” and an “honest and reputable” businessman. He referred to Trump as a “gentleman in every way” and called the real estate baron’s limousine series “spectacular.”

Schwartz also recalled that, years after the limo licensing deal, Trump wrote a letter of recommendation on behalf of his son, who was seeking admission to the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton business school, Trump’s alma mater. “I had asked him casually and he said, ‘No problem,’” Schwartz said. Later, in connection with a Florida business deal, Schwartz said he asked Trump if he could “use his name as a testimonial.” Trump granted permission, Schwartz said, telling him, “Jack, my pleasure.”

“He’s a loudmouth, but so is everyone else,” Schwartz said of the Republican presidential candidate.

* * *

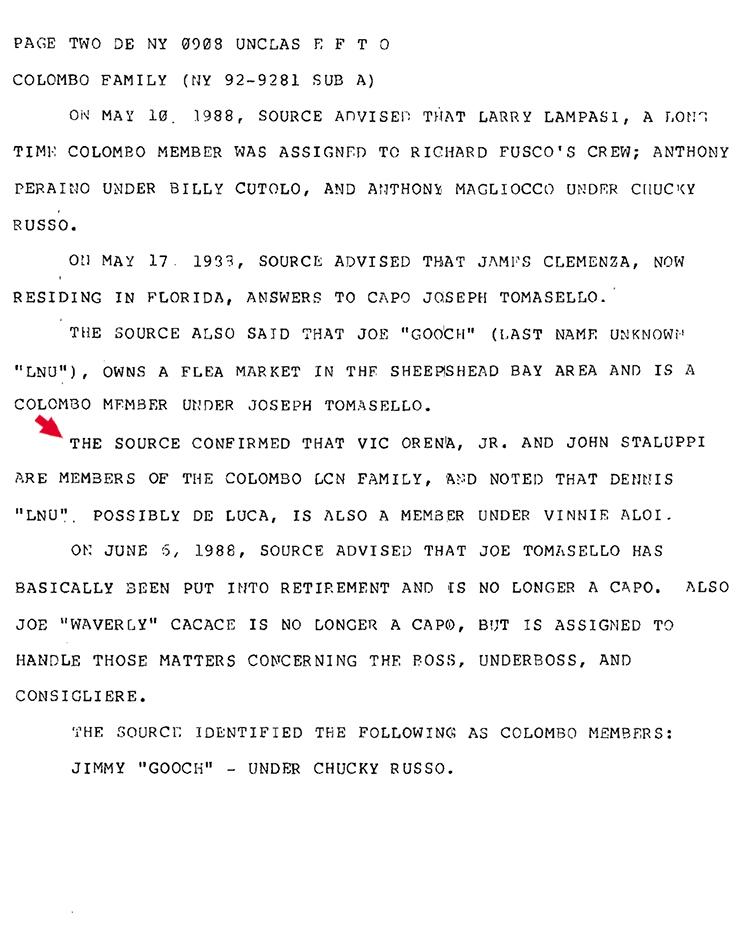

FBI records show that as production was beginning on the Trump limousines in early-1988, agents were discussing Staluppi with Colombo captain Gregory Scarpa, a top echelon informant who for years had been providing federal investigators with an unparalleled view inside the Colombo family and other Mafia outfits.

During a May 1988 conversation with his FBI handler, Scarpa “confirmed” that Staluppi and a second man “are members of the Colombo LCN family,” according to an FBI memo. “LCN” is the acronym for La Cosa Nostra.

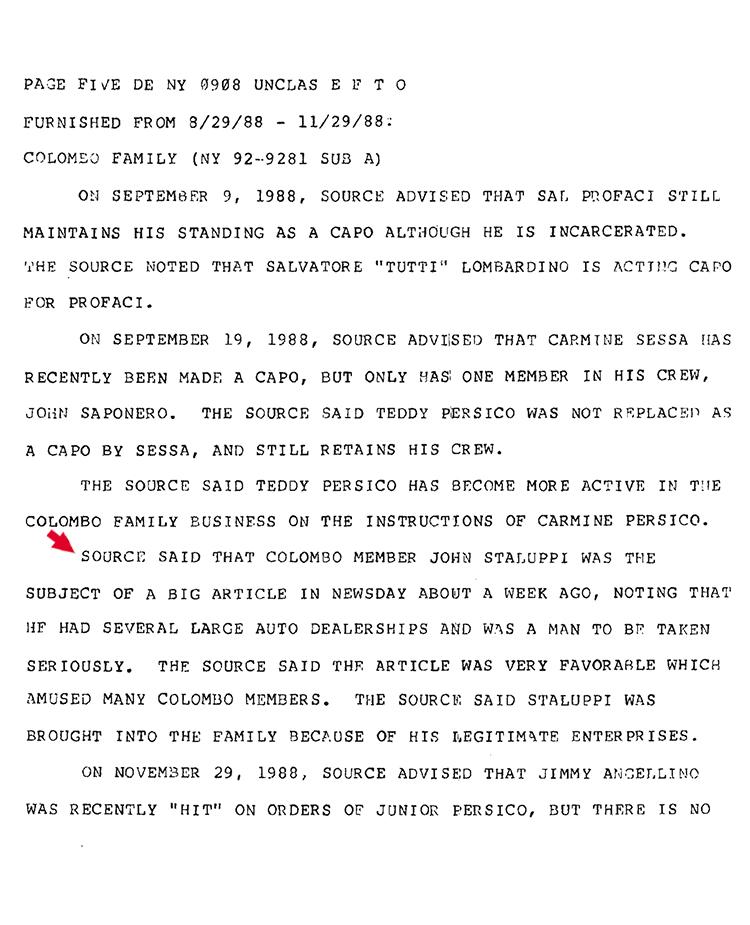

Four months later, in September 1988, Scarpa was again reporting on Staluppi, this time prompted by a 2800-word story on the auto dealer that appeared in the September 15 issue of  Newsday.

Newsday.

The glowing profile focused on Staluppi’s lucrative auto dealerships and his extravagant lifestyle, which included ownership of Cigarette boats, jet airplanes, helicopters, a succession of mega yachts (which he named after James Bond movies like “Moonraker” and “For Your Eyes Only”), and homes in Long Island, Palm Beach, and upstate New York. While the newspaper profile of the “speed freak” Staluppi included no mention of his criminal past, his Mafia ties, or his work with Trump, it did note that Staluppi was planning a hunting trip to British Columbia, where he hoped to kill a grizzly bear.

As detailed in an FBI memo, Scarpa (seen above) reported that the Newsday piece described Staluppi as a “man to be taken seriously.” Scarpa--whom the FBI described as one of the “most valuable organized crime sources operated” by the bureau’s New York office--said that, “the article was very favorable which amused many Colombo members.”

Scarpa told his handler that, “Staluppi was brought into the family because of his legitimate enterprises.”

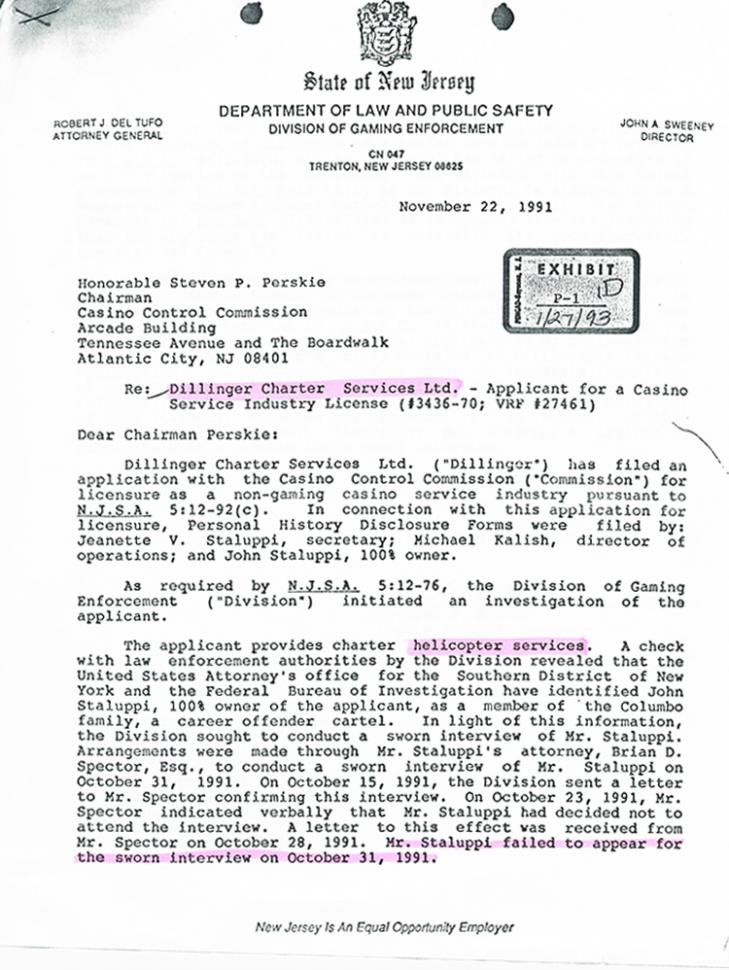

In mid-1991, New Jersey casino regulators began investigating Staluppi when he filed for a license to operate a helicopter charter business servicing Atlantic City’s casinos. During the previous year, his firm, Dillinger Charter Services, did in excess of $600,000 worth of business with casino licensees.

While probing Staluppi, Division of Gaming Enforcement agents copied his phone book, which included contact information for Trump, as well as Colombo family members like acting boss Victor Orena, captain Theodore Persico, and soldiers Rosatti and Amato. Stapled at the back of the book was an invitation to the July 1991 wedding of Colombo captain Dominic “Donny Shacks” Montemarano’s  daughter.

daughter.

Sadly, the father of the bride (left) had to miss the nuptials since he was serving a racketeering sentence at the federal prison in El Reno, Oklahoma.

Staluppi’s helicopter licensing bid was eventually rejected after federal law enforcement officials identified him as a “member of the Colombo family, a career offender cartel.” Staluppi did not help his case by declining to submit to a sworn DGE interview.

But when state officials subsequently sought to bar him from even entering a casino, Staluppi mounted a defense, fearful that such a banishment would hurt him with bankers and prohibit his attendance at auto industry events in Atlantic City.

During sworn testimony, Staluppi acknowledged his business ties with a range of Colombo family members, but denied that he himself was a gangster. Staluppi also made sure to mention that he built the Trump limousines, and that he socialized with The Donald. “I was on his boat, he was on my boat,” said Staluppi. At the time, Staluppi’s boat was the 132-foot “Octopussy,” while Trump’s vessel was a 282-foot yacht he purchased from the Sultan of Brunei and renamed “Trump Princess.”

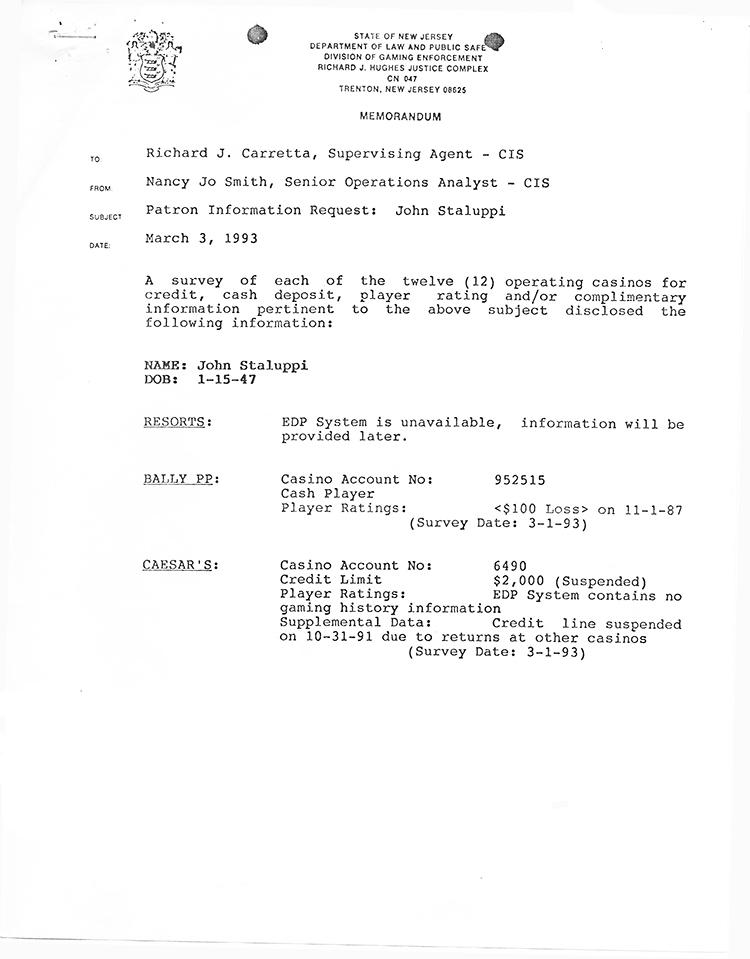

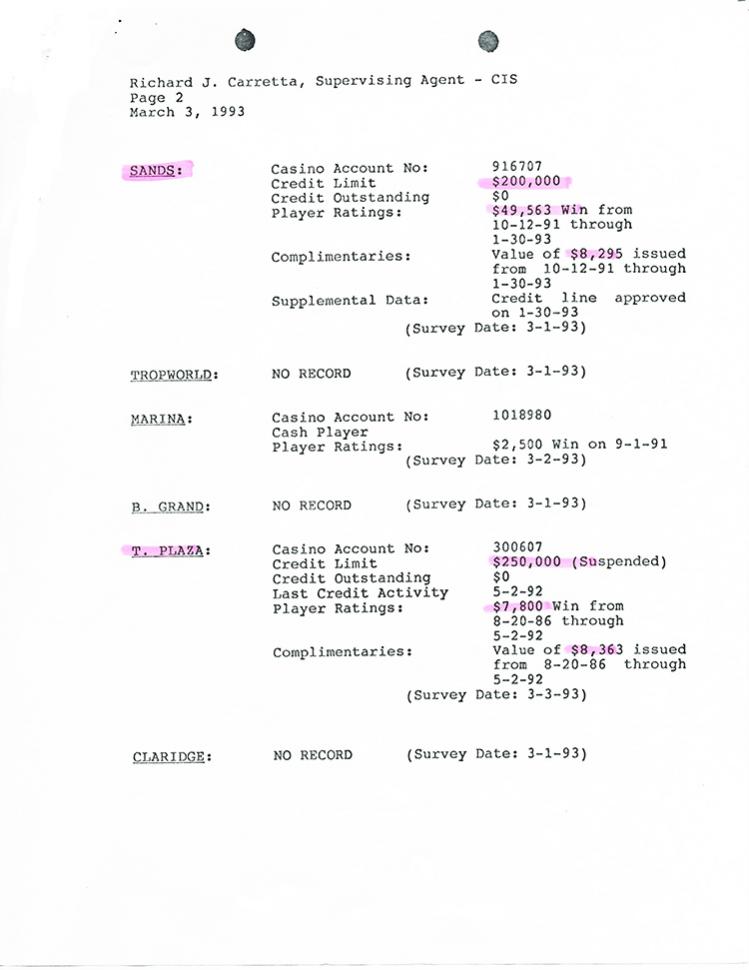

Staluppi was also a frequent gambler at Trump’s casinos, according to records obtained by DGE. Staluppi began betting at Trump Plaza at least two years before striking the limousine licensing deal with Trump. The wiseguy was given $250,000 credit lines at each of Trump’s three casinos, and he received $216,813 worth of complimentary chips and services from the Trump properties (as of early-1993).

While a supervisor in the FBI’s organized crime unit testified that Staluppi was a made member of the Colombo family, the Casino Control Commission eventually declined to place him  on the Atlantic City exclusion list. Agent Brian Taylor’s refusal to identify the FBI’s sources of information on Staluppi--which included informant Gregory Scarpa--crippled the case against Staluppi.

on the Atlantic City exclusion list. Agent Brian Taylor’s refusal to identify the FBI’s sources of information on Staluppi--which included informant Gregory Scarpa--crippled the case against Staluppi.

* * *

Staluppi’s business interests appear to have made him one of the richest organized crime figures ever. One published report estimated his net worth at $400 million, though it is unknown how that figure was determined.

According to Automotive News, Staluppi’s 32 dealerships had a combined $2.8 billion in revenue in 2014, and the publication lists him as the country’s ninth-largest new car dealer. In July, Staluppi commissioned an Italian firm to build his latest yacht (which will cost in the tens of millions of dollars). Last month, the mob soldier listed his sprawling Colorado ranch for sale at $28.95 million. In the foothills of a San Juan Mountains range, the 2800-acre property includes an 8076-square-foot main house and a pool house with a gym, bar, and dance floor with a disco ball.

The auto magnate’s main residence is a Palm Beach Gardens mansion on the Intracoastal Waterway, not far from buddy John Rosatti’s own waterfront compound. Staluppi lives about 18 miles north of Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s 20-acre Palm Beach estate (and future Southern White House).

In November 2009, Trump and Staluppi appeared together onstage at Mar-a-Lago during a James Bond-themed charity dinner benefitting the Boys & Girls Clubs of America. Trump, honorary chairman of the “007 James Bond Gala,” and Staluppi, a major donor, each were presented with framed artworks in recognition of their contributions to the fundraiser. A photo from the black tie dinner shows Staluppi’s wife Jeanette between her husband and the beaming billionaire.

Staluppi has extensive real estate holdings in New York and Florida, where one of his 2012 transactions was flagged by The Palm Beach Post.

Staluppi bought a West Palm Beach strip club from a company managed by Thomas Farese, seen below, the Colombo family consigliere who was previously convicted of using the business to  launder money. The club is now operated by Staluppi’s son-in-law, who built a second West Palm Beach strip joint on a property purchased by Staluppi for $1.9 million in 2013.

launder money. The club is now operated by Staluppi’s son-in-law, who built a second West Palm Beach strip joint on a property purchased by Staluppi for $1.9 million in 2013.

But despite his well-documented Mafia pedigree, Staluppi’s business does not appear to have suffered as a result of his Colombo family affiliation. News stories about Staluppi focus on his dealerships, yachts, classic car collection, and charitable endeavors. There are only scattered references to organized crime, in part because Staluppi has not been touched by any of the numerous law enforcement roundups that have weakened the Colombo family since its last internal war broke out more than 20 years ago.

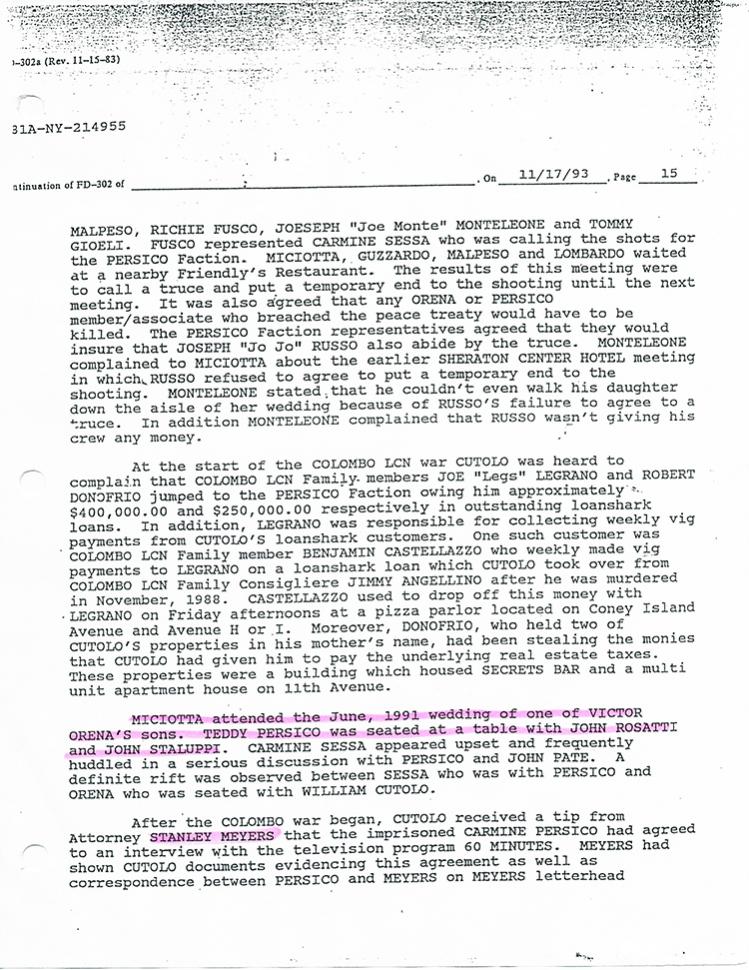

That street battle pitted members loyal to imprisoned boss Carmine Persico against hoods aligned with acting boss Victor Orena, who was seeking to supplant Persico.

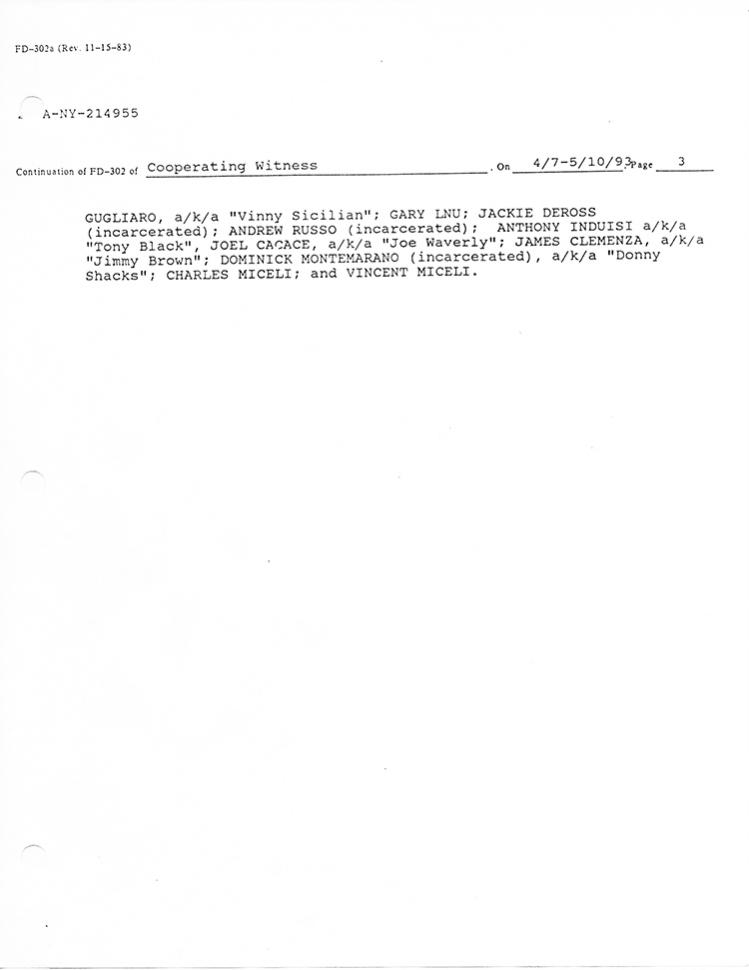

As a result of the bloody combat--which left more than a dozen wiseguys dead--an array of Colombo family members abandoned the gang in favor of striking cooperation deals with the Department of Justice. Several of those hoodlums spoke about Staluppi during debriefing sessions with FBI agents.

Colombo captain Carmine Sessa, who briefly served as the family’s consigliere, gave agents a detailed outline of the crime group’s structure, and named Staluppi and Rosatti as members of the crew headed by Carmine Persico’s son Theodore. Colombo captain Salvatore Miciotta recalled attending the June 1991 wedding of one of Orena’s sons and seeing Staluppi and Rosatti seated at a table with Theodore Persico. A year earlier, Staluppi and Rosatti were spotted at the wedding reception of Camine Persico’s nephew Lawrence, according to a law  enforcement surveillance report. Accountant Kenneth Geller, who did work for an assortment of hoodlums, told the FBI that Staluppi co-owned a car dealership with Camine Persico’s son Michael and sold a dealership to Orena’s sons.

enforcement surveillance report. Accountant Kenneth Geller, who did work for an assortment of hoodlums, told the FBI that Staluppi co-owned a car dealership with Camine Persico’s son Michael and sold a dealership to Orena’s sons.

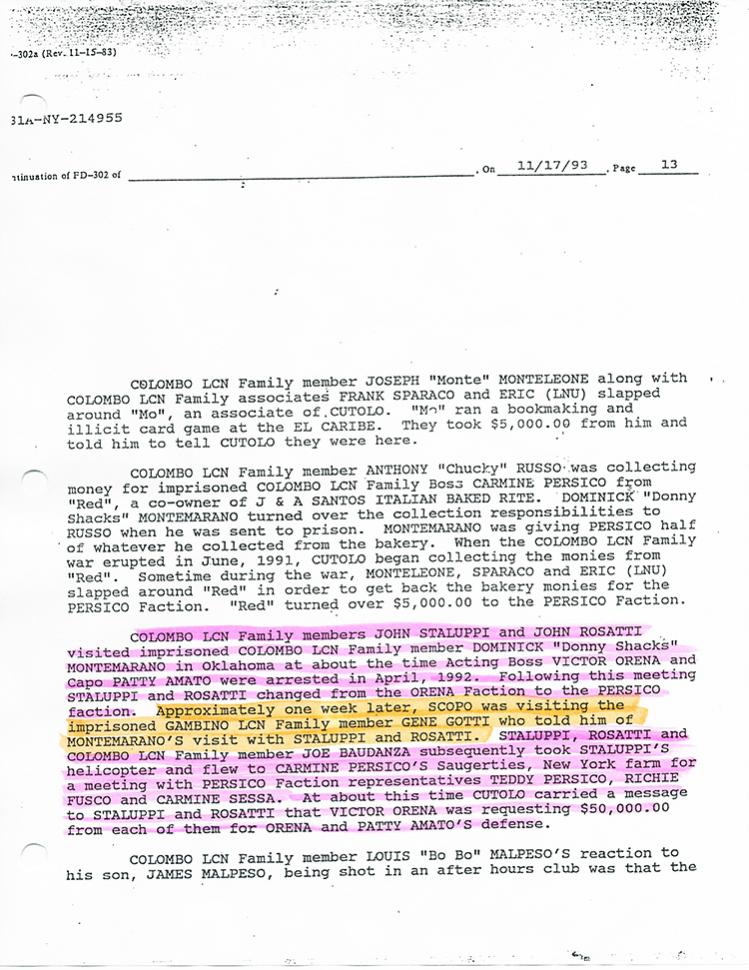

Several turncoats also revealed how Staluppi and Rosatti had originally backed Orena at the outset of the Colombo war, but switched sides in the middle of hostilities.

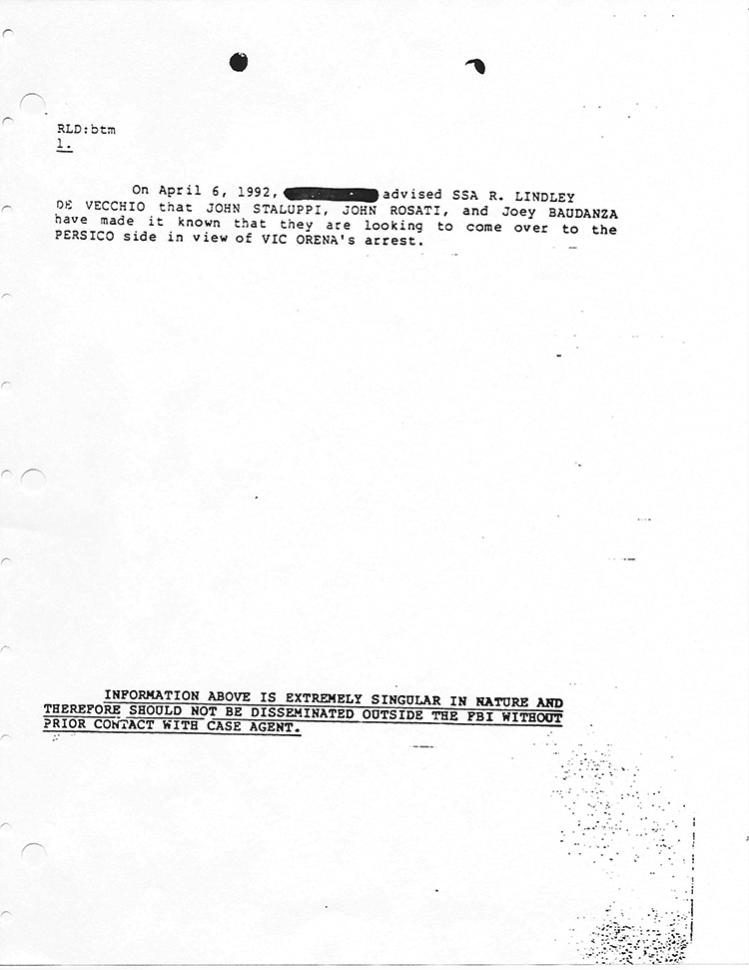

Scarpa contemporaneously reported that the duo “made it known that they are looking to come over to the Persico side” in light of Orena’s April 1992 arrest. After Miciotta began cooperating in late-1993, he told FBI agents that Staluppi and Rosatti flipped after paying a jailhouse visit to veteran Colombo member (and Persico loyalist) “Donny Shacks” Montemarano.

Following the Montemarano sitdown, Staluppi, Rosatti, and a third wiseguy flew in Staluppi’s helicopter to Carmine Persico’s upstate New York farm for a meeting with Theodore Persico, Sessa, and other “Persico faction representatives,” Miciotta reported. Pictured above, Carmine Persico, 82, is currently being held in a federal prison in North Carolina. His scheduled release date is March 2050.

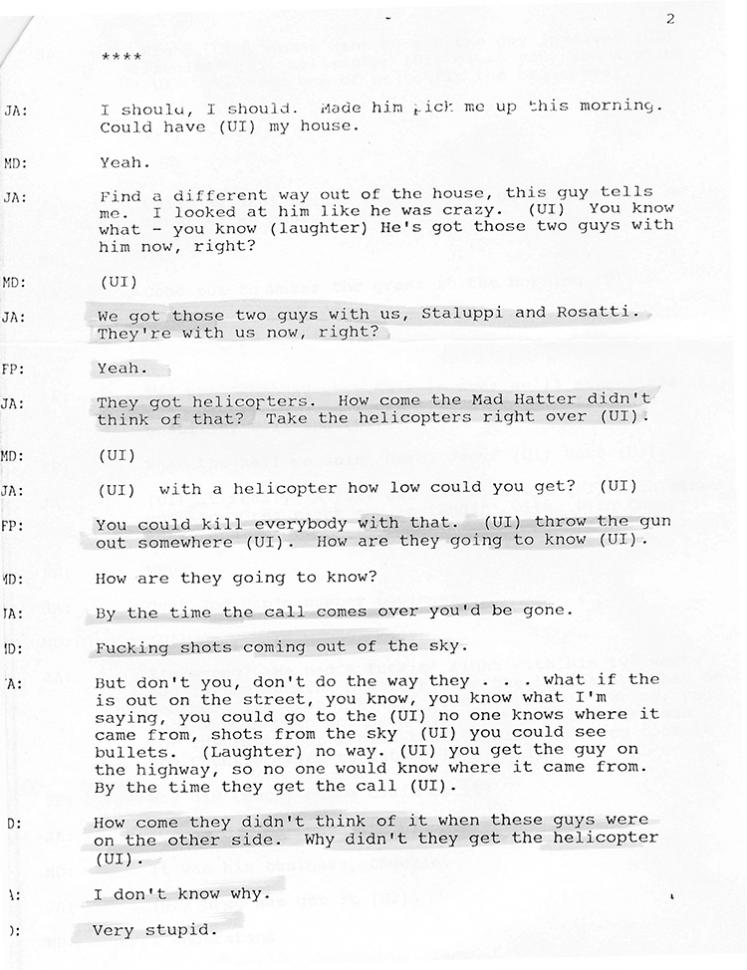

The Staluppi/Rosatti change of heart was also the subject of a bugged June 1992 conversation between three Persico supporters. “We got those two guys with us, Staluppi and Rosatti. They’re with us now, right?” one hoodlum asked his cohorts, one of whom answered, “Yeah.” Referring to the wealthy car dealers, one gangster remarked, “They got helicopters.” The trio then wondered why choppers were not being used in the Colombo war effort. “You could kill everybody with that,” one man remarked, while another added, “Fucking shots coming out of the sky.” (23 pages)