Poster Child For College Cheating Scandal

Tawdry tale of how Californian got into USC

View Document

![]()

MARCH 14--While most parents kept their offspring in the dark when it came to the illegal steps being taken to rig admission to top colleges, one child of privilege was all in when it came to brazenly cheating her way into school, records show.

Amber Zangrillo, 20, whose father Robert was arrested Tuesday on a federal fraud charge, is the poster child of the nationwide cheating scandal.

Zangrillo’s father, a Miami-based venture capitalist and real estate developer, has been accused of paying $250,000 to illegally get his youngest daughter  into USC as a transfer student.

into USC as a transfer student.

Zangrillo, a debutante who once competed in equestrian events, applied for admission to USC in 2017, but her application “was rejected,” according to a U.S. District Court filing. While Zangrillo attended the private Laguna Blanca School in Santa Barbara during her freshman and sophomore years, it is unclear from which high school she eventually graduated.

After failing to get accepted by USC, Amber (seen at right) did not begin matriculating at a four-year college in 2017. Instead, she apparently took online classes via Ria Salado College. However, as alleged by federal prosecutors, Zangrillo and her father kept their sights on USC despite have already received a rejection letter.

Which is how William Rick Singer entered the picture.

Singer, 59, was the mastermind of the college cheating ring that resulted this week in the arrest of dozens of parents and college coaches and administrators. Singer, who has been cooperating with federal investigators, pleaded guilty Tuesday to multiple felony charges related to the scheme. Court papers do not reveal how the Zangrillos met Singer or whether the consultant had previously been used by the family (Amber’s older sisters are recent graduates of USC and NYU).

In the wake of Amber’s rejection by USC, prosecutors charge, Singer told Zangrillo’s father that he could arrange her acceptance to the Los Angeles school as a transfer student by falsely claiming that she was a crew team recruit. Amber, however, had never rowed (and her original application to USC made no mention of her purported crew bona fides).

After the transfer application was submitted to USC in early-2018, the Zangrillos had a conference call with Singer and Mikaela Sanford, one of the consultant’s employees. The conversation was secretly recorded pursuant to a wiretap authorization for Singer’s phone that was secured by the FBI and federal prosecutors.

During the call, Singer detailed the USC scheme for the Zangrillos, noting that the school’s crew team coach had agreed to designate Amber as a “purported recruit to the crew team.” At one point, Amber asked the consultant what he was doing to rectify an “F” grade she had  received in an online art history course. Singer assured her that Sanford, 32, was almost done retaking the class in Amber’s stead. Asked by Singer if that plan made sense, “Zangrillo and his daughter both replied, ‘Yes,’” investigators reported.

received in an online art history course. Singer assured her that Sanford, 32, was almost done retaking the class in Amber’s stead. Asked by Singer if that plan made sense, “Zangrillo and his daughter both replied, ‘Yes,’” investigators reported.

Zangrillo’s 52-year-old father (pictured at left) then asked if Sanford “could also take his daughter’s biology class as well.” Sanford replied that she was “happy to assist.” Zangrillo requested that “the biology thing” get done quickly and “then you do the best you can to overturn the art history [grade].”

In mid-June 2018, Zangrillo received an offer of admission as a transfer from USC. She would begin classes in the 2019 spring semester--which started in early-January. Zangrillo’s admission, prosecutors allege, was greased by Donna Heinel, a USC athletics official who was indicted this week for racketeering conspiracy. Heinel, who was fired by USC following her arrest, is accused of taking $1.3 million in bribe payments from Singer.

In a June 26 e-mail to Singer, Heinel said that she had not actually presented Zangrillo to the school’s admissions department as an athletic recruit, but instead placed Amber “on our VIP list for transfers.”

Upon his daughter’s acceptance to USC, Zangrillo wired $200,000 to a charitable front group controlled by Singer. The businessman also sent a check for $50,000 to the university’s women’s athletics department.

In the weeks after her transfer acceptance, Amber updated her Facebook page to indicate “Started School at University of Southern California.” The news was greeted with congratulations from friends and her maternal grandmother. Zangrillo’s social media pages show her vacationing, traveling on a private jet, and sunbathing on the deck of her father’s waterfront Miami mansion (her family also has homes in Aspen, Hollywood, Santa Barbara, and New York City).

[Following the publication of this story, Zangrillo’s Facebook page was stripped of all its photos and posts, including the July 2018 announcement of her USC acceptance.]

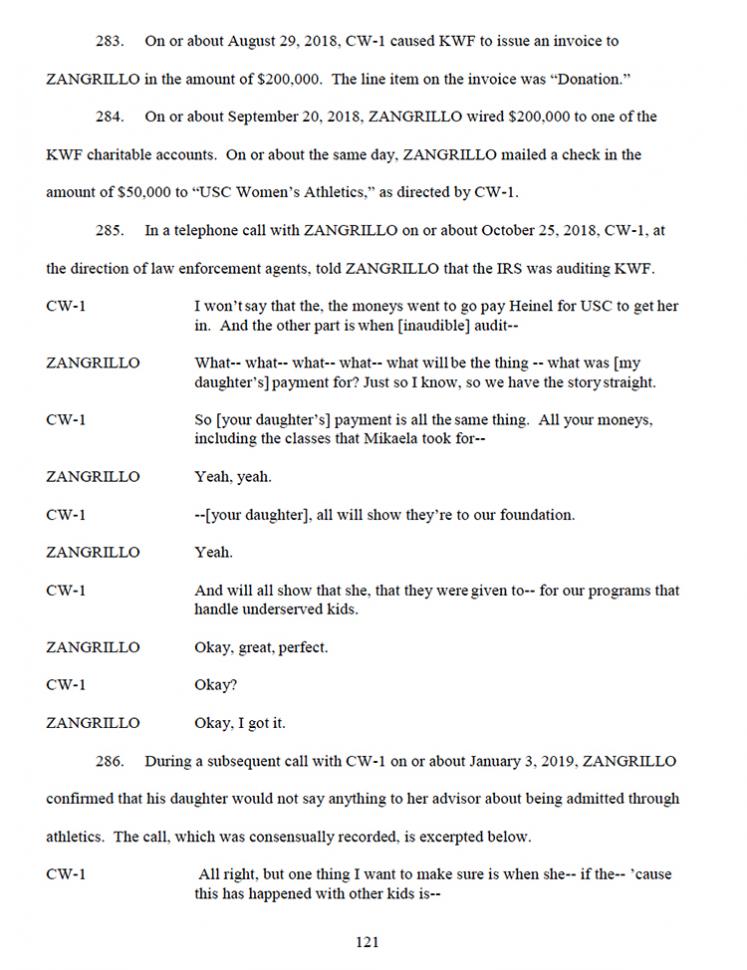

USC officials said yesterday that it will bar admission to about six student applicants connected to Singer’s consulting business. Administrators will also conduct case-by-case reviews of current students--presumably like Zangrillo--who had already been admitted. Additionally, monies donated to USC by Singer clients will be redirected to fund scholarships for underprivileged students, the school announced. (5 pages)