The Dapper Don's Drab Duds

How TSG obtained a prison uniform worn by the Mafia boss

View Document

John Walters Check Defraud Scheme

-

John Walters Check Defraud Scheme

-

John Walters Check Defraud Scheme

-

John Walters Check Defraud Scheme

-

John Walters Check Defraud Scheme

-

John Walters Check Defraud Scheme

John Walters Unocal Fraud

-

John Walters Unocal Fraud

-

John Walters Unocal Fraud

-

John Walters Unocal Fraud

-

John Walters Unocal Fraud

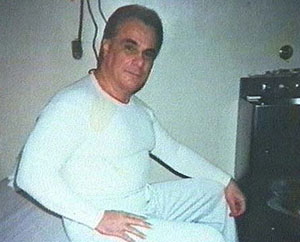

During the decade John Gotti spent behind bars following his 1992 racketeering conviction, only one photo surfaced showing him in the can. The snapshot captured the Mafia boss relaxing in his cell at the federal penitentiary in Marion, Illinois. Along with a smirk, the gangster is wearing a long-sleeve t-shirt and sweatpants, items he purchased from the prison commissary's limited clothing collection. Gotti would also occasionally slip into a red jumpsuit, which he was required to wear during visits with family members and his legal team.

During the decade John Gotti spent behind bars following his 1992 racketeering conviction, only one photo surfaced showing him in the can. The snapshot captured the Mafia boss relaxing in his cell at the federal penitentiary in Marion, Illinois. Along with a smirk, the gangster is wearing a long-sleeve t-shirt and sweatpants, items he purchased from the prison commissary's limited clothing collection. Gotti would also occasionally slip into a red jumpsuit, which he was required to wear during visits with family members and his legal team.

But the staple of the wiseguy's wardrobe was a standard-issue khaki uniform, the dull outfit of federal inmates everywhere. With its 65% polyester/35% cotton blend and boxy cut, the uniform didn't offer Gotti the kind of stylish menace that came with the double-breasted Brioni suits he once favored. In fact, those prosaic threads were both the stylistic and symbolic counterpoint to Gotti's flashy, yet failed, tenure as head of New York's Gambino crime family. Sartorially, the Dapper Don had been reduced to the Drab Don.

What follows is the story of how The Smoking Gun recently obtained a uniform Gotti wore at Marion, khakis that were taken by an inmate working in the penitentiary laundry shortly after Gotti was permanently transferred to the federal medical center in Springfield, Missouri. The FBI and Bureau of Prisons have opened formal investigations into the possible theft of Gotti's uniform, according to BOP officials and another TSG source.

In the days following the mob figure's June 10 death, TSG began monitoring eBay auctions of Gotti memorabilia, ranging from jailhouse correspondence to New York newspapers announcing his demise. For the most part, eBay quickly shut down offerings for letters, autographed photos, and any other items the online giant considered offensive--a standard eBay practice when auctions involve controversial subjects or questionable taste.

On the morning of Monday, June 24, a TSG reporter noticed a new Gotti auction, one that had been posted the prior evening (and which would subsequently be yanked early Monday afternoon). Headlined "John Gotti Prison Items," the auction description read, "John Gotti's actual worn khaki shirt and pants from Marion Federal Penitentiary with his prison name and register number on them (iron-on inmate tag), John Gotti's actual laundry bag with his name and register number on it (iron-on inmate tag), and a handwritten note by John Gotti to the laundry staff at the prison." The seller--who sought an opening bid of $2200 in the seven-day auction and posted no photos of the items--had no prior sales, purchases, or feedback listed on eBay.

Using eBay's "ask seller a question" feature, two TSG reporters separately sought further details about the provenance of the purported Gotti items. With the exception of coming right out and saying we were journalists chasing an intriguing story, TSG did little to mask our identity in subsequent correspondence with the seller: we used our own pre-existing eBay accounts, provided the seller with TSG's fax number, and gave a post office box number that, via a simple Google search, came right back to the web site. One reporter even provided the seller with his name, a Google search for which would have quickly turned up his TSG employment and, to boot, his role in exposing a famous eBay sham.

Were we sloppy in covering our tracks? Probably. But TSG prefers to leave the cloak and dagger stuff to others. And, as it turned out, we weren't the only ones hiding in plain sight.

Responding to our initial e-mails, the seller immediately offered to fax a copy of the Gotti note and mail photos of the other items once they were developed. When the fax came to the first reporter, it was accompanied by a Kinko's cover sheet listing the sender as John Walters. In short order--following a search of federal court records--TSG identified a former Marion inmate named John Walters who was living in the same Chicago suburb as the eBay seller. A simultaneous check of prison records revealed that Walters's Marion stay overlapped with Gotti during the mobster's final five months in Illinois.

In further e-mail exchanges about the Gotti items, the seller, who identified himself only as John to the second reporter, wrote that, "I worked in the prison laundry at Marion for a period of time while [Gotti] was there." He added, "I brought them out of the prison in Marion personally." Asked whether the items might be considered government property, John replied, "no one can claim ownership of the items except me, I was allowed to take them out of the prison as mine.....neither the federal prison system nor the Gotti family can claim ownership whatsoever." While not saying it explicitly, John's e-mails left little doubt that he was an ex-con. Who else works in a prison laundry?

At this point, TSG showed a copy of the one-page note purportedly written by Gotti to the Marion laundry staff (it dealt with the mundane matter of a sheet and pillow case exchange) to a lawyer who had worked for the late Gambino boss. The verdict was swift and came with no hesitation: "That's his handwriting," said the attorney, who regularly exchanged correspondence with Gotti. TSG also provided a copy of the handwritten document to Victoria Gotti, the late gangster's daughter, who disputed that her father authored it. She pointed to the fact that the note had a number crossed out, something she claimed her meticulous dad would never do. Gotti, a mystery novelist and New York Post columnist, has long claimed the government railroaded her father, who she recently eulogized as a "New York icon" and "legend."

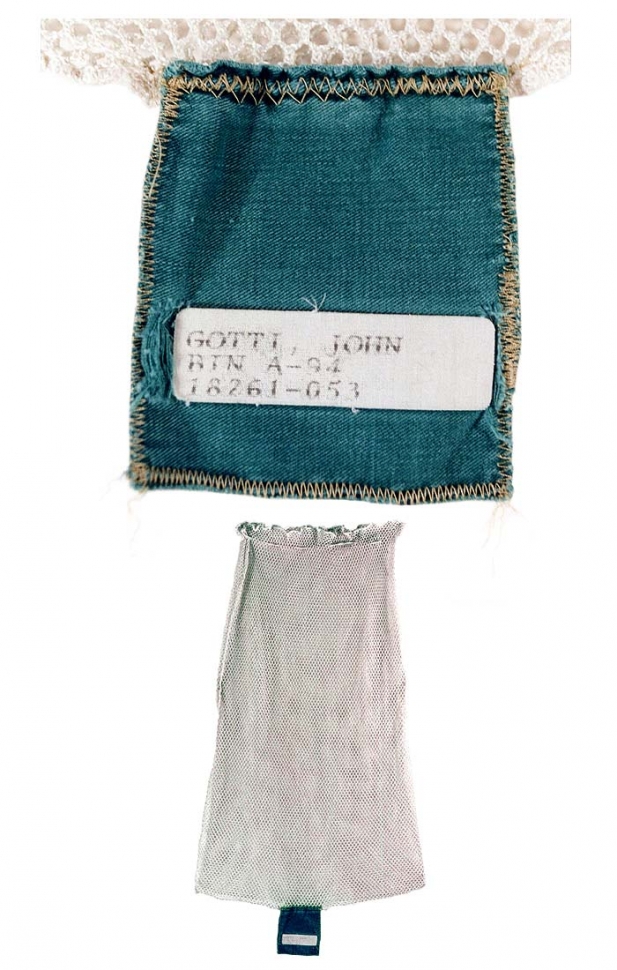

Within days, the seller mailed envelopes containing photos of the garments to both TSG reporters (and mentioned in e-mails that he was sending similar pictures to several other prospective bidders who had contacted him prior to eBay removing his auction). Taken with a disposable camera and developed at Walgreens, the photos were no works of art, but appeared to show a classic khaki prison uniform, with the pants carrying a name tag affixed at the belt line above the right back pocket. It read:

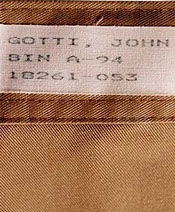

GOTTI, JOHN

Bin A-94

18261-053

The iron-on identification tag and its placement were consistent with a detailed khakis description that had been provided to TSG by a current Marion penitentiary inmate, who relayed uniform details via his attorney. Gotti's federal prison register number, according to BOP records, was 18261-053. And, as TSG would later learn, an individual bin number is assigned to inmates so that laundered items can be efficiently sorted and returned to them.

The handwritten note faxed by John Walters included Gotti's correct register number, the A-94 notation, and a Marion cell location identified as "C-C-7." On June 24, the same day Walters faxed TSG the handwritten Gotti note, we forwarded it to Kevin Murphy, executive assistant to Marion's warden, who said he was providing the document to the prison's "investigative staff." However, since then, BOP officials have refused to say whether Gotti's bin number and cell location matched those listed on the note (which Walters said was authored in August 2000). Instead, they have referred our questions to the BOP's Freedom of Information unit, which will likely take weeks--at the very least--to provide any information.

By late-June, TSG confirmed that the man seeking to sell the Gotti items was the same John Walters who was incarcerated in Marion's low-security prison camp from April 2000 to October 2001. In fact, when Walters mailed photos to one TSG reporter, he included a return address that matched up with one recently provided to probation and court officials by the former Marion inmate.

Walters, 43, pleaded guilty in September 1999 to orchestrating a check-kiting scheme that netted him about $20,000 during mid-1997. According to prosecutors, Walters used counterfeit checks to "open accounts and cause enough confusion with the banks that he was able to pull a substantial amount of money out of those accounts before the fraud was detected." For that scam, Walters spent about 18 months in Marion before being released into a halfway house, where he remained until April 2002.

The 1999 guilty plea was Walters's second white-collar conviction. In March 1996, he was indicted for ripping off $285,000 from Unocal, where he worked as an administrative supervisor. Walters admitted approving dozens of phony invoices and having payment sent to a fictitious company he had created. For this fraud, Walters spent a year in the prison camp at Oxford, Wisconsin. The Unocal invoice scheme, which occurred between 1993 and 1995, subsidized a Walters spending spree that saw him squire one girlfriend to "expensive locations," according to prosecutors.

Federal investigators also alleged that Walters, who is divorced and has sole custody of his teenage son, would even sometimes claim to be an FBI agent, in an apparent bid to impress women. Court records also reveal that Walters spent about 12 years in the Marine Corps, re-upping on two occasions. But he left under a cloud in the late-1980s, receiving a general discharge for allegedly mishandling confidential documents.

So the possibility that Walters was somehow cooking up an eBay scam involving bogus Gotti items could not be ignored. But since he had just begun a five-year probation term and made little attempt to shield his identity, it seemed that a scheme rooted in multiple instances of apparent wire and mail fraud was particularly reckless (especially since the items would only net him $2000).

It appeared more likely to TSG that Walters had authentic Gotti items. The notion that an inmate would help himself to some potentially valuable souvenirs after the mobster shipped out, well, that shouldn't surprise anyone. It certainly wouldn't be the first time that an article of clothing got pinched in Marion, where currency comes in many forms and propriety and decorum are in short supply.

So TSG decided that the only way to determine whether the Gotti uniform, laundry bag, and letter were legitimate was to try and buy them (and, if successful, closely scrutinize the four items). Did we want to part with two grand for a murderous racketeer's duds? Certainly not, since the prospect of actually handling the hoodlum's khakis gave us the creeps.

In e-mails, Walters noted that he wanted to complete a sale by July 4, but declined requests made by TSG reporters (who were separately corresponding with him) to meet in person to close the deal. Walters wrote that he preferred to carry out the transaction through the mail--which TSG was not going to do.

So, at that point--late on the evening of July 2--a TSG reporter sent Walters an e-mail unveiling himself as a journalist working on a story about the Gotti items and the circumstances by which Walters obtained them. Anticipating no response, TSG reporters--working from a hotel near Walters's home--prepared to confront the ex-con.

But Walters did the unexpected, writing back to provide his home phone number and agreeing to interviews (one of which occurred on the telephone that night and another took place in person the following morning, when TSG purchased the Gotti items for $2000). In those interviews and following e-mail exchanges, Walters argued that he got the Gotti material legally, but acknowledged employing a fair degree of subterfuge to first obtain the items, and then get them out of Marion upon his release last October.

Since the nearly 450 inmates housed in the Marion penitentiary are held under the second-highest degree of security in the federal system, work details are manned entirely by residents of the adjoining 330-person prison camp, a low-security facility. Among other jobs, camp inmates handle groundskeeping, maintenance, cafeteria, and repair shop chores. Along with several other camp inmates, Walters was assigned to the laundry room, which is located "inside the wall" at the penitentiary. "I was housed in the camp across the street," said Walters, "and was brought into the prison and brought out."

According to Walters, the day after Gotti--who had been battling cancer--left Marion for Springfield in mid-September 2000, items left behind in his cell were sent to the laundry, where they were to be washed and "recycled." Along with the khakis, Walters said he noticed that Gotti somehow had obtained socks and underwear--briefs, not the standard-issue white boxers--that were not available in the prison commissary (he took a pass on pinching the don's drawers, however). Asked what happens to the contents of a prisoner's cell when they are relocated, BOP spokesperson Linda Smith said, "Generally when inmates leave the facility these items are returned to general inventory/stock and re-issued to other inmates."

But before that could happen, Walters admitted, he "grabbed" the khakis and the bag and "rolled them up and put them on a shelf" in the laundry. He did this because he recognized that the items "would be worth something someday, especially when Gotti died." Walters added this was the same motivation that led him, a month earlier, to pocket the brief note Gotti had sent to the laundry staff.

Walters said that he worked in the "main laundry area" for six months, beginning in mid-June 2000. He was then detailed to the prison tailor, working in a room "on the other side of the laundry" until he left Marion. Walters said that he moved the Gotti pieces to "a shelf in the tailor office when I was assigned there." Official BOP documents obtained by TSG confirm that Walters was employed in Marion's laundry, where he worked as a "laundry machine operator." Those BOP records also indicate that Walters's "work performance ratings" were described as "outstanding."

The prospect that an inmate waltzed out of Marion with Gotti's uniform is apparently a source of great embarrassment to BOP brass. After initially providing limited answers to TSG questions about BOP procedures and uniform details, prison officials deflected our requests. For example, when TSG asked prison officials for certain details about Walters's imprisonment, BOP spokesperson Smith said that the information was not public. But she added in an e-mail, "If you obtain signed release/authorization from the inmate, the information will be supplied." At our request, Walters then provided TSG with a notarized release granting permission for us to access information from his inmate file. But when we forwarded the Walters release to Smith, she informed us, for the first time, that the matter would be handled as a FOIA request, a process that can take weeks to complete.

The BOP stonewall was so complete that when a reporter asked Smith about inmate laundry bags (What do they look like? Is there a closure mechanism? Are they mesh?), she responded with an e-mail announcing, "We are unable to provide the information you request." Smith's reason for the denial was fabulously specious: "The degree of specificity requested is viewed as potentially creating security concerns for the institution." Apparently, a public dissemination of confidential laundry bag details could trigger a rampage at Marion, where guards already have their hands full trying to stop homicides, rapes, and gang activity.

Walters said that a few weeks before his October 9, 2001 release, he asked a laundry supervisor for permission to take a spare set of khakis (which, he claimed, he would wear following his release into a Chicago halfway house). Walters said his supervisor agreed and signed an inmate request form, known colloquially as a "cop-out." Walters readily admitted that he never told the Marion administrator that the khakis he was carrying out of the laundry room carried John Gotti's name.

After stashing the Gotti items in his locker at the prison camp, Walters asked his counselor for permission to leave Marion with the set of khakis, a laundry bag, and a few other items. The counselor agreed, Walters said, and signed the same cop-out he previously presented to the laundry supervisor. Again, he made no mention of who once wore the threads (and whose name remained on the pants, shirt, and laundry bag). BOP spokesperson Smith confirmed that an inmate "may make a special request through his unit team and case management coordinator for khakis work clothing. Formal permission is needed and the permission would be in writing."

The signed cop-out was Walters's get-out-of-jail-with-a-free-set-of-khakis card. "I showed the items and the cop-out form to the R&D [Reception & Discharge] officer, he said ok, and I put them back into my bag and I was taken to the bus station in Marion," Walters recounted in one e-mail. Walters said he tossed the signed cop-out, of which he thought he had the only copy, after arriving at a Salvation Army halfway house. Smith noted that typically only cop-outs addressing "more important issues such as medical, dental, mail, visitation, legal matters, etc. are maintained" in an inmate's central file.

The Walters rationale for his deception boils down to: they didn't ask, so I didn't tell. This is, of course, rather disingenuous considering that he acknowledges plucking the items from a Marion laundry tub while Gotti was still settling into his new Missouri digs. While Walters believes title to the Gotti items is clear, Murphy disagrees. "They were property of the prison," said the Marion administrator. As such, BOP's Special Investigative Services unit is probing the Gotti khakis case. SIS Agent Danny Shoff, who works out of Marion, declined to answer TSG questions about the internal investigation.

For his part, Walters, who is on probation, seemed only mildly concerned that there might be legal reprisals stemming from the Gotti uniform caper (which likely explains why he has made statements to TSG that might be construed as being against his judicial interests).

So, then, what about those khakis? By every measure available to TSG--descriptions provided by a BOP spokesperson, previous newspaper accounts describing Marion uniforms, information relayed from a current penitentiary inmate, and a close examination of the items themselves--the uniform and laundry bag appear to be authentic. As does the handwritten letter.

Both the shirt and pants carry an iron-on tag containing Gotti's name and identification numbers. Compared to a detailed description of a Marion uniform provided to us by Smith, the BOP spokesperson, the Gotti uniform is an exact match. Ditto as to the location of the tags, which are found at the base of the tail of the shirt and at the belt line of the pants, above the right rear pocket.

On the interior of both garments, there is a small ink stamp indicating that the items were made at the federal prison in Oakdale, Louisiana by inmates working for UNICOR, the prison industries firm. According to Smith, the "garments used at Marion…are produced at UNICOR's FCI Oakdale facility," though "normally they do not carry a UNICOR ink stamp."

The Gotti items also exactly match previously published descriptions of Marion uniforms when it comes to belt loops, location and size of pockets, button fly, and polyester/cotton percentages. And as for garment sizes, they also seem to match the Gambino boss's proportions. The shirt is a large, with a 34" sleeve. And the pants have a 40-inch waist and a 30-inch length--just about what you'd expect for the stout, 5' 9" gangster.

In an interview Saturday (7/13), Victoria Gotti questioned the authenticity of the items, claiming that her father did not wear a khaki uniform during his seven-plus years at the Illinois penitentiary. When she traveled to Marion, of course, Gotti only saw her father dressed in the red jumpsuit inmates were required to wear during visits. Gotti decried the items--which she had not seen--as fake and said, "I would stake everything I have on it." It seems that the daughter of the late hoodlum--who was once an accomplished truck hijacker--can't imagine another felon boosting a load.

If you're wondering what TSG will do with the Gotti items, well, they'll be filed away just like any of the material we gather reporting a story. We won't be displaying the uniform, offering it for sale, or wearing it around the office.

As for Walters, who now works as a salesman, he told TSG he was not mulling any future eBay activity. But he added that his son was bugging him to help auction off some of the teen's Star Trek collectibles and a used Xbox.